Bronze Age Balts

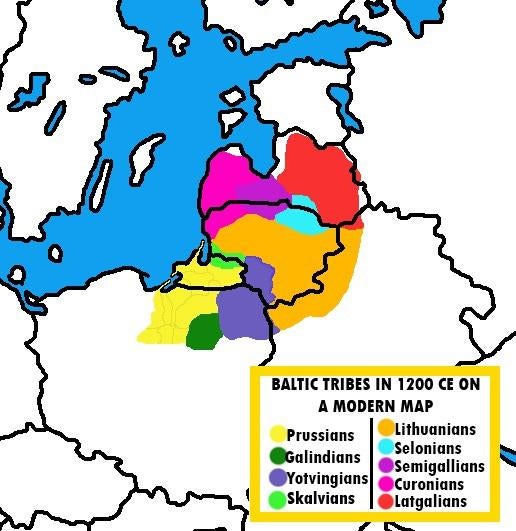

The timeline covered in this article ranges from 1800 BC to 500 BC and describes the territory of what is modern day Latvia, Lithuania, North-East Poland and Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia[1]. The Bronze Age Balts had close contacts with the Nordic Bronze Age, Mycenaean Greeks, Lusatian, Hallstatt and La Tène cultures. The Northern border of their terrtiory from the 9th century BC was protected by the Brikuļi wooden fortress. The invading groups could be different Baltic-speaking clans inhabiting the territory of Bronze Age Estonia or the fortress itself was back then placed in the middle of Baltic territory (R1a-Z280, R1a-M558 and R1a-Z92 united clans) and was simply an important stop in the Northern Baltic trade route, also with Uralic tribes to the North and East.

Around 2000 BC a new wave of inhabitants and novelty comes to the area of Kętrzyn, Poland. A horse bridle and bronze axes were found in Sątoczno, Poland and daggers in Sterławki, Poland. In the peat bogs near Giżycko, Poland a wooden boat from that period, 12 meters long, was excavated. The development of civilization was also associated with an increase in population. The only indicator, but not a fully reliable one, of the population growth in the Kętrzyn area were the cemeteries. The bodies of the dead were either buried whole or burned.

There was a settlement near lake Dusia (Lithuania) around 1000 BC, which belonged to the Brushed Pottery Culture. The oldest settlements considered to be part of Early Brushed Pottery Culture are dated to 1300 BC - 1100 BC, and are found along the rivers Neris and Šventoji in Lithuania. The Brushed Pottery Culture replaced the Narva Culture, which existed in that region until 1700 BC. While traditionally it is believed that the Narva Culture was replaced by the Indo-European influence carried by the Corded Ware Culture, this viewpoint has been challenged, and a distinction is made between Corded Ware influenced Western Baltic Culture, and separate Brushed Pottery Culture[2].

The most recognizable feature of the Baltic Bronze Age culture are hillforts, which were first established circa 1000 BC[3][4]. They are believed to have been able to house from 80 to 120 inhabitants, in rectangle shaped houses of wooden pole construction, and were fortified. 110 hillforts belonging to the Brushed Pottery Culture have been found in the territory of Eastern Lithuania.

Hoards were found along the lower Vistula and in East Prussia which contained inter-regional forms of bronze types which frequently appear in Central Europe and in North-Western Europe. The earliest bronzes were identical to the Únětice and there is no doubt that the Bronze Age was initiated in the South-Eastern Baltic area through influences from Central Europe [Marija Gimbutas, Światowit 23, page 390].

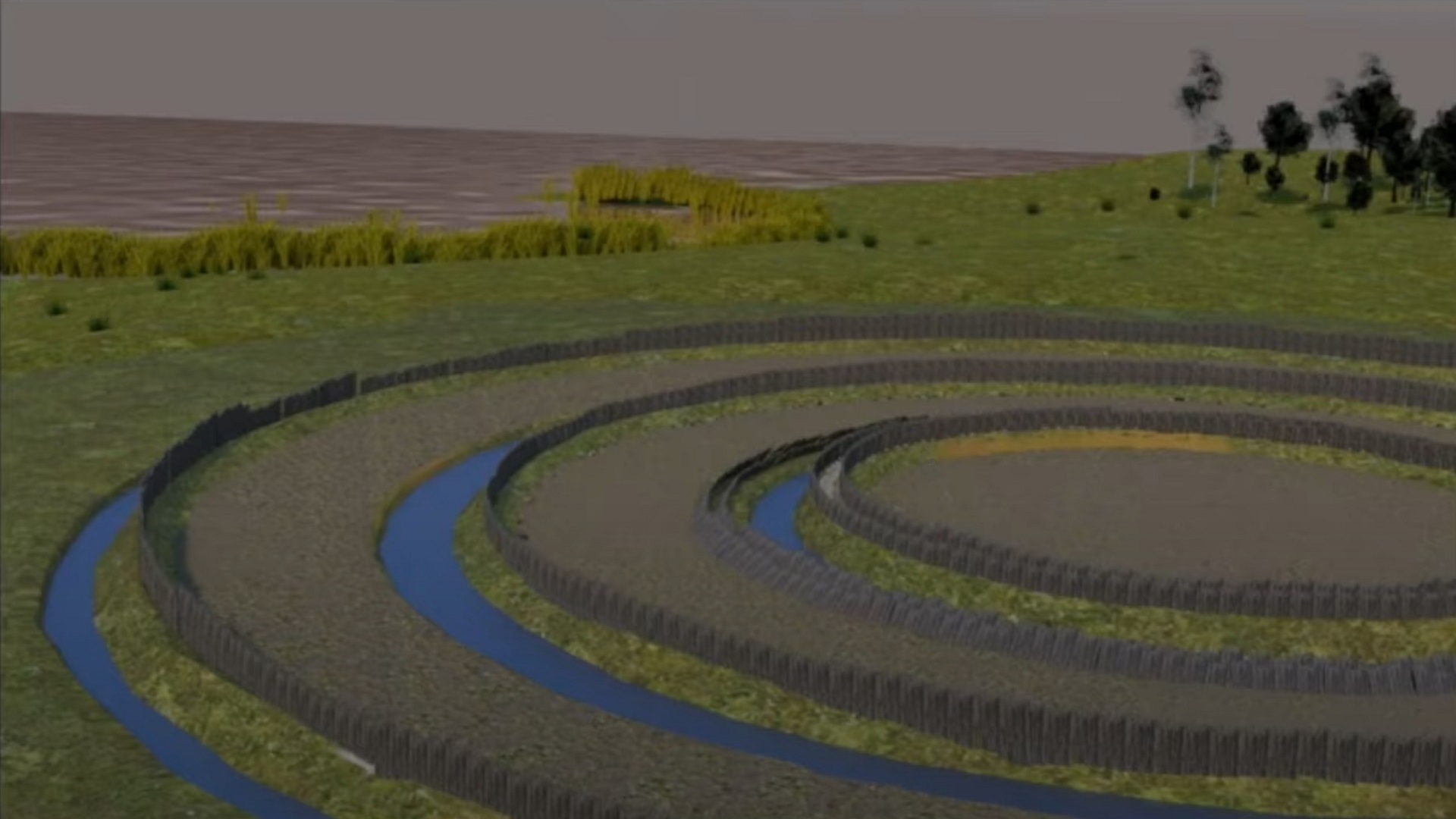

Marija Gimbutas called the period between 1300 BC and 1100 BC the "Classical Baltic Bronze Age Culture". It coincides in time with the efflorescence of the Northern Area Culture (Nordic Bronze Age) in Northern Germany, Denmark, and Southern Sweden. The ceramic art was quite different from the Únětician and Lusatian. Its roots are in the preceding Haffküsten (Rzucewo) Culture. Throughout the whole of the Bronze Age, barrow tombs were constructed encircled by serveral rings of stones, these likewise bear witness to the individuality of this cultural entity. Despite its intensive trade with Central and North-Western Europe, the South-Eastern Baltic Culture continued its individual features through this period and later. It is generally agreed that this archaeological culture belonged to the early Baltic speaking peoples [Marija Gimbutas, Światowit 23, page 392].

Burials

The body of the deceased or their ashes were buried in burial mounds, which for example were discovered in Sterławki Wielkie and Wilkasy, Poland. Cemeteries without burial mounds were discovered in Warzyny near Bartoszyce and in Łężany near Reszel, Poland. Such graves were usually equipped with various gifts, most often vessels containing food.

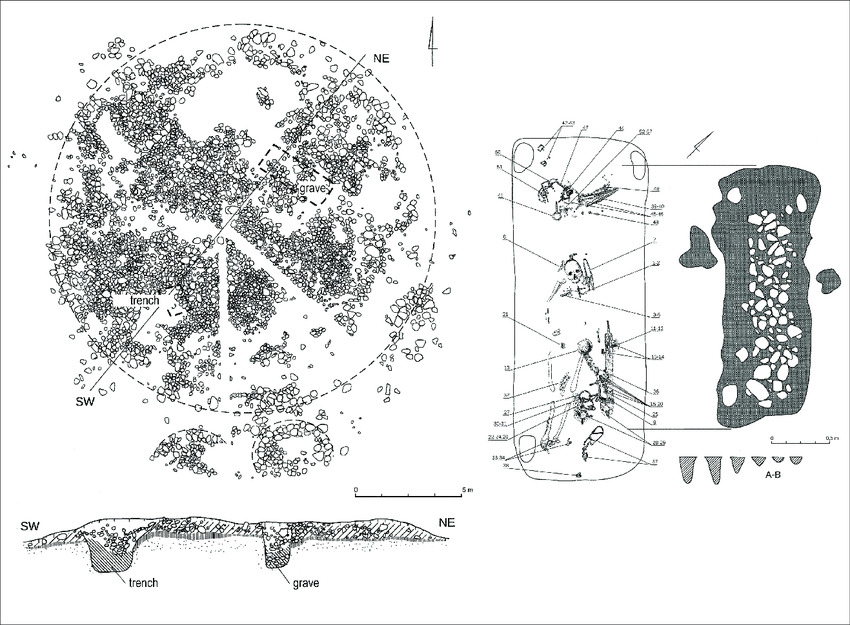

Throughout the Early Bronze Age, uncremated dead were buried in barrows, usually laid on stone floors and covered with stones or with cists built of various sized stones. The barrow was encircled by a ring of stones. A continuity in burial rites is demonstrated by the stratified barrow excavated in 1873 AD in the village of Viskiautai (Mokhovoye), district of Primorsk (Fischhausen), Samland. Graves A—C belonged to the end Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. Judging from a belt clasp of bone, the lowest grave, grave A, belongs to the Baltic Haff (2700 BC Haffküsten, Rzucewo) Culture, which equates in time with the Bell Beaker period. The grave second from the bottom, grave B, contained a rhomboid stone axe, a flint knife and a bone pin with loop - finds typical of the Early Bronze Age (approximately 16th century BC). Grave С was above grave В and contained an ingot torque and a small bronze chisel-like tool. The next grave, grave D, was an urngrave of the Late Bronze Age [Marija Gimbutas, Światowit 23, page 398].

The earliest 1100 BC cremation graves were in imitation of inhumation graves: cremated bones were placed in shallow pits in the center of the barrow. In several instances cremated bones were found scattered over the fire-place. There were no urns. The transition from inhumation to cremation was gradual as in the Lusatian Culture, but in the Southeastern Baltic area it came several centuries later. The earliest cremation graves did not imitate Lusatian urn-graves but showed individuality [Marija Gimbutas, Światowit 23, page 398].

The cemetery in Sorkwity situated in the central part of the Mrągowo Lake District, included 8 cremation graves. They were almost exclusively individual urn burials. The urns, mostly covered with bowls, were placed on little stone pavements. The pottery from Sorkwity is relatively homogenous with respect to its formal and technological characteristics. The analysis of the osteological material showed that charred animal and human bones commonly occur side by side[5].

The analogy to the pottery from the cemeteries in Mojtyny and Biedaszki (Olsztyn province, Poland) indicates that the cemetery in Sorkwity should be dated to the transition period between the 6th and 5th century BC. The examined site is located in the area of a large settlement concentration, which was occupied throughout the whole first millenium BC. Not further than 20 km to the North-West, a settlement microregion has been differentiated. It is dated to the 2nd or 3rd century BC. Its pottery material completely differs from the material found in Sorkwity[5].

Sites and Routes

The most important archaeological sites connected with the Bronze Age Balts are located in Latvia: Bārta Pukuļi, Katlakalns Parumba, Sēja Jaunāmuiža, Sabilē; in North-East Poland: Kosyń, Samławki, Iława, Szczytno, Sątoczno, Giżycko, Rajgród, Sorkwity, Sterławki Wielkie, Wilkasy, Bartoszyce, Łężany, Kępa Tolnicka, Skomętno, Skomack Wielki, Szurpiły, Suchowola; in Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia (Old Prussia): Mokhovoye, Primorsk, Vishnevka, Zaostrove, Kudryavtsevo (Kuglacken), Käswurm Nettienen, Timofeevka (Tammowischken); in Lithuania: Kernavė, Mineikiškės, Šernai, Garniai, Kaunas, Virvyčia, Veliuona, Vilnius.

The bronze figure from Šernai, Lithuania is unique because it is most similar to figures found in Hittite Anatolia, Mycenaean Greece and Lebanon[6]. This and the supposedly Egyptian glass beads from Kosyń, Poland (1550 BC) could support the theory of a lively amber trade route going from the Eastern Baltic through modern day Poland to the Aegean Sea and Anatolia.

Mineikiškės surprised archaeologists with the abundance of finds, especially in comparison with the previously researched Garniai mound (Utena district, Daugailiai eldership). Amulets, axes, jewelry, fragments of earthenware, about 6 thousand ceramic shards of various sizes, many bones. The researchers conclude that the main source of protein for the people who lived there was meat. They raised pigs, which made up about half of the livestock, and kept sheep, goats, and horses. According to one skeleton, the researchers assume that the horsemeat was also consumed.

The following plants were mostly consumed: proso millet (panicum miliaceum), apples (malus sylvestris), wheat (triticum dicoccoides), fava beans (vicia faba), oats, flax, poppy, lentils (lens culinaris), pale persicaria, barley (hordeum vulgare)[7]. Different types of meat included: boar, deer, pig, horse, beef, fish. Their diet did not differ from that of neighbouring Lusatian Culture.

Gallery Of Artifacts

Sanskrit and Baltic

Words common mainly between the Baltic languages and Indo-Aryan languages will be listed at first, which would mean that those words surely were used by people of the Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture and go back as far as 3000 BC or beyond.

- bone: कुल्यम् (kulyam)

- Old Prussian: kaulan

- Latvian: kauls

- Lithuanian: kaulas

- Ancient Greek: καυλός (kaulós) ("shaft, stem")

- chin: श्मश्रु (śmáśru)

- Lithuanian: smakras, smakra

- Hittite: šamankur, zamankur ("beard")

- Old Irish: smech

Notice Satem "śr" in Sanskrit and Centum "kr" in Lithuanian

- horse: अश्व (aśva)

- Old Prussian: aswinan ("horse mare milk")

- black: कृष्ण (kṛṣṇá, krishna)

- Old Prussian: kirsnan

- boy: भ्रूण (bhruna)

- Lithuanian: bernas ("lad"), berniukas ("boy")

- Latvian: bērns

- Gothic: 𐌱𐌰𐍂𐌽 (barn)

- stronghold, fortress, castle: पुर (pura), पुर् (púr), पुरी (purī, puli)

- Latvian: pils

- Lithuanian: pilis

- Ancient Greek: πόλις (pólis) ("town")

This word proves that the concept of building fortresses was not unknown even around 3000 BC or 2500 BC in Central and Eastern Europe.

- who: कः (kah, kaḥ)

- Lithuanian: kas

- Latvian: kas

- Gothic: 𐍈𐌰𐍃 (ƕas)

- Albanian: kush

- Tocharian A: kus

- *Estonian: kes

- cave: वल (vala)

- Latvian: ala

- Latgalian: ola

- Samogitian: ola

- English: well

- *Ainu: ポル (poru, maybe from *volu)

- **Lithuanian: urvas

- rabbit: शशक (śaśáḥ, shashak, zazaka)

- Old Prussian: sasnis

- Latgalian: začs

- Tocharian B: ṣaṣe

- Marathi: ससा (sasā)

- Dutch: haas

- *Khakas: хозан (xozan)

Now a list of words that are also common with mostly Baltic, Slavic, Germanic, Greek and Latin:

Some of them were already covered in detail in the words section: Deva, Mara, Hamsa, Vrika, Mamsa, Sivyati, Bhratr, Nasika, Cakra/Ratha, Pat, Dasa, Sata, Nabhas

- animal, pasture, cattle, livestock: पशु (paśu)

- Old Prussian: pecku (peku) ("animal")

- Lithuanian: pẽkus

- Gothic: 𐍆𐌰𐌹𐌷𐌿 (faihu)

- Old English: feoh, fioh, feh

- Latin: pecū, pecus ("cattle")

- Umbrian: 𐌐𐌄𐌒𐌏 (peqo) ("wealth")

- Polish: paść ("to herd")

- Tocharian A: pās- ("to look after, guard")

- Persian: پاس (pâs) ("guard")

- Latin: pāscō (pasko) ("put to graze")

- *Kabardian: псэущхьэ (psawɕħ, pseushche) ("animal")

- *Polish: pies, psa ("dog" as "animal used for pasture")

That is why Prussian name of Peckols literally meant "The Cattle God" and was equal to Slavic "Veles" in this manner ("Rich in Cattle"). The other name of Peckols could be Patollo (cognate to Hindu Patala), which would mean "Under the Feet", he would then perfectly fit into the image of European Chtonic Underground God of Cattle and Death.

- stone: अश्मन् (aśman)

- Lithuanian: akmuo, ašmuo, ašmenys

- Latvian: akmens, asmens

- Ancient Greek: ἄκμων (ákmōn) ("anvil, pestle, battering ram")

- Polish: kamień (inverted "ak" to "ka")

- fire: अग्नि (agní)

- Bengali: অগ্নি (ôgni)

- Old Church Slavonic: огнь ⱁⰳⱀⱐ (ognĭ)

- Latin: ignis

- Lithuanian: ugnìs

- Old Prussian: ugnis

- Kashmiri: اۆگُن (ogun)

- Polish: ogień

- Lower Sorbian: wogeń

- Latvian: uguns

- coal: अङ्गार (áṅgāra)

- Pashto: انگار (angār)

- Old Prussian: anglis

- Lithuanian: anglìs

- Latvian: ògle

- Old Church Slavonic: ѫгль ⱘⰳⰾⱐ (ǫglĭ)

- Silesian: wōngel

- Polish: węgiel

- Czech: uhel

- tooth: दन्त (dánta)

- Lithuanian: dantis

- Old Prussian: dantis

- Old Breton: dant

- Avestan: dantan

- Persian: دندان (dandân)

- Swedish: tand

- Old Dutch: tant

- Greek: δόντι (dónti)

- Gothic: 𐍄𐌿𐌽𐌸𐌿𐍃 (tunþus)

- Oscan: 𐌃𐌖𐌍𐌕𐌄 (dunte)

- Latin: dēns, dentēs

- Old East Slavic: дѧсна́ (dęsná) ("gums of teeth")

- Serbo-Croatian: де̑сни, dȇsni ("gums of teeth")

- Slovak: ďasno ("gums of teeth")

- living: जीवित (jīvita, zhivita), जीव (jīva, žīva)

- Lithuanian: gývas

- Old Prussian: gijwans, geiwans

- Latvian: dzīvs

- Serbo-Croatian: живети, живјети, živeti, živjeti

- Hindi: जीवी (jīvī)

- Bulgarian: жив (živ)

- Latin: vivus

- Greek: bios

The exchange of "G" = "ZH" = "DZ" or rather more common and softer "K" = "S" = "DS" here present in the "purely" Satem languages and denying whole Centum / Satem idea

- right: दक्षिण (dákṣiṇa)

- Avestan: dašina ("right, south")

- Lithuanian: dešinė, į dešinę

- Old East Slavic: деснъ (desnŭ)

- Bulgarian: де́сен (désen)

- Ancient Greek: δεξιός (dexiós)

- Latin: dexter

- Ossetian: дӕсни (dæsni) ("skillful, dexterous")

- broad, wide, flat: पृथु (pṛthú, prathu)

- Lithuanian: platus

- Latvian: plats

- Ancient Greek: πλᾰτύς (platús), Plato

- Old Norse: flatr

- Old Saxon: flat

- Avestan: pərəθu, perethu

- Polish: płaski, płat

All meanings of this word in Sanskrit: broad, wide, expansive, extensive, spacious, large, great, important, ample, abundant, copious, numerous, manifold, prolix, detailed, smart, clever, dexterous

- when: कदा (kada)

- Latvian: kad

- Old Prussian: kaden

- Serbo-Croatian: ка̏д, ка̀да, kȁd, kàda

- Belarusian: кадэ (kade)

- Avestan: kadā

- Polish: kiedy, kady

- Slovak: kedy

- where is?: कुत्र अस्ति (kutra asti?)

- Albanian: ku është?

- Lithuanian: kur yra?

- Slovak: kde je?

- Polish: gdzie jest?

- Avestan: kudā asti?

- water: उदन् (udán)

- Old Prussian: undan

- Latvian: udens

- Polish: woda (uuoda)

- young: युवन् (yúvan)

- Old Prussian: yuwan

- Lithuanian: jaunas

- Avestan: yauuan

- Persian: جوان (javān)

- Latin: iuvenis

- Old Church Slavonic: юнъ (junŭ)

- Polish: junak

- German: Jung

- name: नामन् (nā́man)

- Old Prussian: emmens

- Old East Slavic: имѧ (imę)

- Polish: imię (imien, emen)

- Slovak: meno

- Ashkun: nām

- Gothic: 𐌽𐌰𐌼𐍉 (namō)

- Kamviri: nom

- Ancient Greek: ὄνομα (ónoma)

- Tocharian A: ñom

- Latin: nōmen

- Hittite: 𒆷𒀀𒈠𒀭 (lāman)

- to sing: गायति (gāyati)

- Polish: gaić

- Latvian: dziedāt

- Lithuanian: giedati

- Lithuanian: gaida ("singer")

- to fart: पर्दते (párdate)

- Kashubian: piardnąć

- Belarusian: пярдзе́ць (pjardzjécʹ)

- Bulgarian: пърдя́ (pǎrdjá)

- Polish: pierdzieć

- Ancient Greek: πέρδομαι (pérdomai)

- Albanian: pjerdh

- Altmärkisch: fort (*pord)

- Latvian: pir̂st

- Lithuanian: persti

- dark: तामस (tāmasa), तिमिर (timira)

- Lithuanian: tamsus, tamsà

- Serbo-Croatian: та́ма, táma

- Polabian: ťåmă

- Latin: tenebrae

- Old Polish: ćma ("darkness", from *tima)

- Latvian: tima

- Old East Slavic: тьма (tĭma)

- Slovak: tma

- Belarusian: цьма (cʹma)

- Upper Sorbian: ćma

Here तामस (tāmasa) is used to also describe someone "ignorant" or "stupid" just like in Polish word "ciemny" is used both meaning "dark in mind".

- ass: پیزی (pīzī)

- Old Prussian: peisda

- Latvian: pīzda

- Lithuanian: pyzdà

- Old East Slavic: пизда́ (pizdá)

- Serbo-Croatian: пи́зда, pízda

- Polish: pizda

- Czech: pizda

- Albanian: pidh

- Nuristani: pəṛī

- Sanskrit: पशु (pasu, pazu)

- udder, belly: ऊधर् (ū́dhar), उदर (udara)

- Old Prussian: weders

- Latvian: vēders

- Bengali: উদর (udôr) ("belly")

- Old English: ūder

- Ancient Greek: οὖθαρ (oûthar)

- Latin: uterus

- Latin: ūber

- Old East Slavic: вѣдро́ (vědró) ("bucket")

- Belarusian: вядро́ (vjadró) ("bucket")

Here the "W" = "V" = "U" = "UU" supports the older sound of Polish "woda" as "uuoda" above or even "uuden".

Sanskrit and Slavic

Some words indicate that Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture originated between Balts and Slavs rather than almost entirely in the terrtiory of Lithuania or Prussia. It was most likely the territory close to the Carpathian Mountains (earliest R1a-Z93 in Europe), and from there circa 3000 BC the Corded Ware Culture tribes moved towards what is now Belarus, Lithuania and Latvia, and then moved further East to Fatyanovo, Russia[8]. Some words in common with Sanskrit not present in the Baltic languages but present in the Slavic languages are:

- to fall: पद्यते (pádyate), पद्यति (pádyati)

- Polish: padać

- Slovene: padec

- Bulgarian: падение (padenie)

- Avestan: paidiiāite

- **Latvian: kritums

- **Lithuanian: rudenį, lietus ("fall of water")

The oldest form of this word would then be "padiati" or "padiać"

- to kill, to reap: हन्ति (hánti)

- Polish: żąć (from *santi or *žąti)

- Russian: жать (žatʹ), сжать (sžatʹ)

- Slovak: žať

- Church Slavonic: жѧти (žęti)

- --? Arabic: حَصَدَ (ḥaṣada)

Maybe this word comes from the Anatolian Farmers (Early European Farmers) just like the word for aurochs: "tur"

- to fight: युध्यते (iúdhiate, yúdhyate)

- Polish: judzić

- Avestan: yūiδiieiti (iudieiti)

- Belarusian: ю́дзіць (júdzicʹ)

- Ukrainian: ю́дити (júdyty)

- great, mighty, strong, abundant: मह (mahá)

- Tocharian B: māka

- Gothic: 𐌼𐌰𐌷𐍄𐍃 (mahts)

- Albanian: madh

- Avestan: mazah

- Hittite: mēkkis, nakkit

- Ancient Greek: μέγᾰς (mégas)

- Old Armenian: մեծ (mec)

- English: much

- Latin: magnus

- Czech: moc

- Old Church Slavonic: мощь (moštĭ)

- Polish: mnogi, moc

- Slovak: mnohý

- Irish: minic

- the screamer: रावण (Ravana, Rabana)

- Polish: raban ("loud noise, scream")

He was breaking the law of people and gods. He exposed himself to Shiva by trying to move Mount Kailasa, where Shiva was hugging his wife Parvati. The indignant Shiva, pressing the mountain to the ground, pinned Ravana's hands. The expression of his pain was so terrible that it was then that he gained his nickname Ravana - Screamer, Howler.

- to learn: उच्यति (úcīati)

- Old Church Slavonic: оучити (učiti)

- Polish: uczyć się

- Slovene: učíti

- **Lithuanian: mokyti

- to begin work, to work: रभते (rabhate)

- Serbo-Croatian: ра́бити, rábiti ("to use")

- Czech: robit ("to do")

This word can be used in the following Sanskrit sentence: "yas tu nā*rabhate karma kṣipram bhavati nirdravyaḥ", meaning "He indeed who does not begin work soon becomes poor".

The lack of swords...

In 2009 AD a bronze flanged axe was found on the right bank of the Pala river near the confluence of Mūša and Pala in Pakruojis Eldership, Lithuania. The axe is 14.3 cm long, weighs 340 g, and has a 6.9 cm wide blade and a 2.3 cm wide butt. Archaeologist Elena Grigalavičienė has recorded 18 such axes in Lithuania's modern day territory, which date to periods III-IV of the Bronze Age.

In 2008 AD, information was also obtained that part of a bronze socketed axe (the blade and eroded socket) had been found in the vicinity of Vaškai, on the right side of the Joniškis – Žeimelis – Pasvalys highway, before reaching the town of Vaškai. This could be part of the Vaškai hoard, which is widely known in archaeological literature and a more precisely identified findspot would provide additional data about the hoard's location. These finds supplement the data about bronze axe findspots in North Central Lithuania.

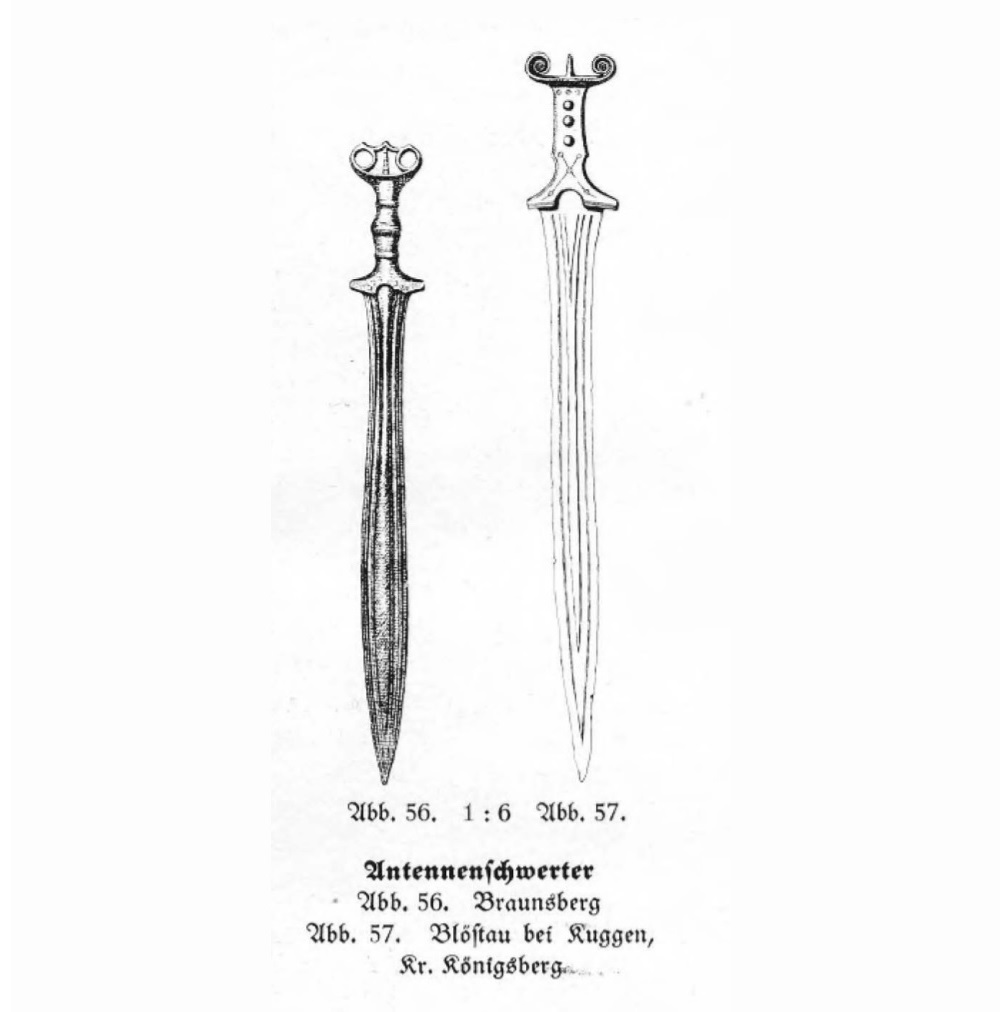

It is thought that there were no bronze swords discovered in the Baltic territory (mostly axes like in the examples above) but one 85 cm long bronze sword was found before the World War II in Atkamp, Rossel, Prussia (nowadays Kępa Tolnicka, Poland). Two bronze antenna swords shown on the right image come from the Rostek near Gołdap, Poland (Braunsberg, Prussia) and Blöstau bei Ruggen (Vishnevka, Kaliningrad Oblast) and there was also one flange-hilted sword discovered in Rantava (Zaostrove).

The accumulation of bronze swords found in the territory of Old Prussian tribes could suggest that the West Baltic tribes gathered most resources and wealth from the amber trade, maybe some of their warriors worked as mercenaries in other parts of Europe as well.

The lack of words

- sword

- Lithuanian: kalavijas, kardas (similar to Ossetian кард, kard)

- Latvian: zobens

- Polish: miecz

- Sanskrit: करवीर (karavira)

from zobs ("tooth, sharpness, blade"), the original meaning was "piercing instrument with sharp edge". Closest Slavic words are: Old Church Slavonic зѫбъ (zǫbŭ) ("tooth"), Polish ząb ("tooth"), Sanskrit: जम्भ (jámbha, zhambha).

There is no cognate for a sword in the Indo-European languages, which means that surely the Indo-Aryan R1a-Z93 migration took place before the year 2000 BC and Bronze Age in Europe but also that a sword most probably came from warrior to warrior in Europe as a war bounty.

- axe

- Lithuanian: kirvis

- Latvian: cirvis

- Sanskrit: परशु (paraśú, parazu)

- Ancient Greek: πέλεκυς (pélekus)

- Basque: aizkora

- Belarusian: сяке́ра (sjakjéra), тапо́р (tapór)

- Persian: تبر (tabar)

- Latin: ascia, secūris

Only Persian word is connected to Slavic and Sanskrit word to Greek here, most probably different Hunter-Gatherer tribes had their own name for this ancient tool.

Old Prussian DNA

The Tolkien family belonged to Y-DNA haplogroup R1a-Z92 from West Baltic branch (R1a-Y42738* from R1a-YP350*)[9]. According to Ryszard Derdziński the Tolkien name comes from the Old Prussian place-name Tollkeim (from *Talkaims). A number of other theories on the meaning of the name have been proposed, including that it is derived from the village of Tolkynen (Tołkiny, Poland) in East Prussia. The Tolkien family originated in the East Prussian town Kreuzburg near Königsberg (modern Slavskoye, Kaliningrad), where the Tolkien name is attested since the 16th century. The verified paternal line of J. R. R. Tolkien starts with Jacob Tolkien, born around 1550 AD near Kreuzburg.

The Nienałtowski family belongs to Y-DNA haplogroup R1a-Z282, other family originating from Prussian nobleman Sklodo, namely Skłodowski family, belongs to R1a-Z92 (from R1a-Z280)[10]. The Derdziński family Y-DNA is R1a-YP350 (it formed around 1 AD from Baltic R1a-Z92)[11].

Common Y-DNA haplogroups from the terrtiory of Podlasie, Poland near the old lands of Jatvingians are: R1a-Z280, R1a-M458, R1a-Z92, R1b-U106, I1a, N1c, I2a1, I2a2[12]. In general the same results came from a similar study on people who had ancestors in the lands of Prussia: 10% of I2a2, 40% of N1c1, 40% of R1a, 10% of R1b[13][prusowie.pl website]. For example there were listed 3 typical Polish R1a-M458 samples, 4 R1a-PH1509 (from R1a-Z280), 1 R1b-L23 and 1 R1b-Z202. The oldest sample from Dollkeim-Kovrovo Culture (100 AD - 600 AD) was determined to be R1a.

Lithuanian and Latvian DNA

One sample named Spiginas2 from Lithuania dated to 2130 BC - 1750 BC belonged to R1a-M558 (CTS1211 from R1a-Z280). Two men from Turlojiškė, Lithuania from 1010 BC (Turlojiske3) and from 930 BC (Turlojiske1) were found to belong to Y-DNA R1a1a1b (R1a-Z645) and in some sources determined to be R1a-Z92 (Y4459, YP617). Sample Spiginas25 from around 800 BC was also determined to be R1a-M558 (CTS1211 from R1a-Z280). The 7 samples from Kivutkalns, Latvia from 730 BC to 500 BC were: R1b1a2 (R1b-M269), R1a, R1a1a1b, R1a1a1b, R1a1a, R1a1a, R1a1[14].

3 samples from Kivutkalns from 805 BC - 230 BC were deeper determined to the following subclades of Y-DNA R1a-Z280: CTS1211 (R1a-M558), YP1034 (from R1a-M588, people who carry this haplogroup nowadays live in Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Sweden, Russia[15]), Y13467 (same as YP1034 but younger and formed around 1800 BC[16]). None of examined male Bronze Age individuals carry the Y-DNA haplogroup N, which is found in modern Europeans in highest frequencies in Finland and the Baltic states, instead the high frequency of R1a Y-DNA is observed[17].

The most common mtDNA samples (around 1000 BC to 200 BC) from the same study were: U5a1c1, U5a1a1, U5a2a1, U5a2a1, H1c, H1b2, H1b1, H28a, H10a, H5, H4a1a1a3, T2b, T1a1b, J1b1a1[17].

Already around 5460 BC a man from Donkalnis7 in Lithuania carried the Y-DNA haplogroup R1* and mtDNA U5a2d1[18]. 4200 BC male samples from Zvejnieki, Latvia carried: Y-DNA R1b-M269 and mtDNA U4a1; Y-DNA I2a2a1b and mtDNA U5a1c Y-DNA R1b-M269 and mtDNA U4a1[19]. Even older sample from the same Zvejnieki site from around 7465 BC carried Y-DNA R1b-M269 and mtDNA U5a2c[20]. Close to Zvejnieki, a man from Tamula3, Estonia from around 3800 BC carried Y-DNA R1* and mtDNA U4d2. Gyvakarai1, Lithuania sample related to the Corded Ware Culture from around 2620 BC carried Y-DNA R1a1a1* (R1a-M417) and mtDNA K1b2a[21].

Since the Neolithic, the native population of what would become Lithuania has not been substituted by other peoples. Thus, the origin of the contemporary Lithuanian population may be traced back to the Neolithic settlers, with little admixture hereafter[22]. Lithuanians positioned as the closest present-day European population to three different pre-Neolithic Hunter-Gatherer groups (the Western European, the Scandinavian and the Eastern European) and showed high proximity to the Steppe and Late Neolithic Bronze Age (LNBA) European samples, but far from Sardinia, Anatolia, Armenia and Levant[23].

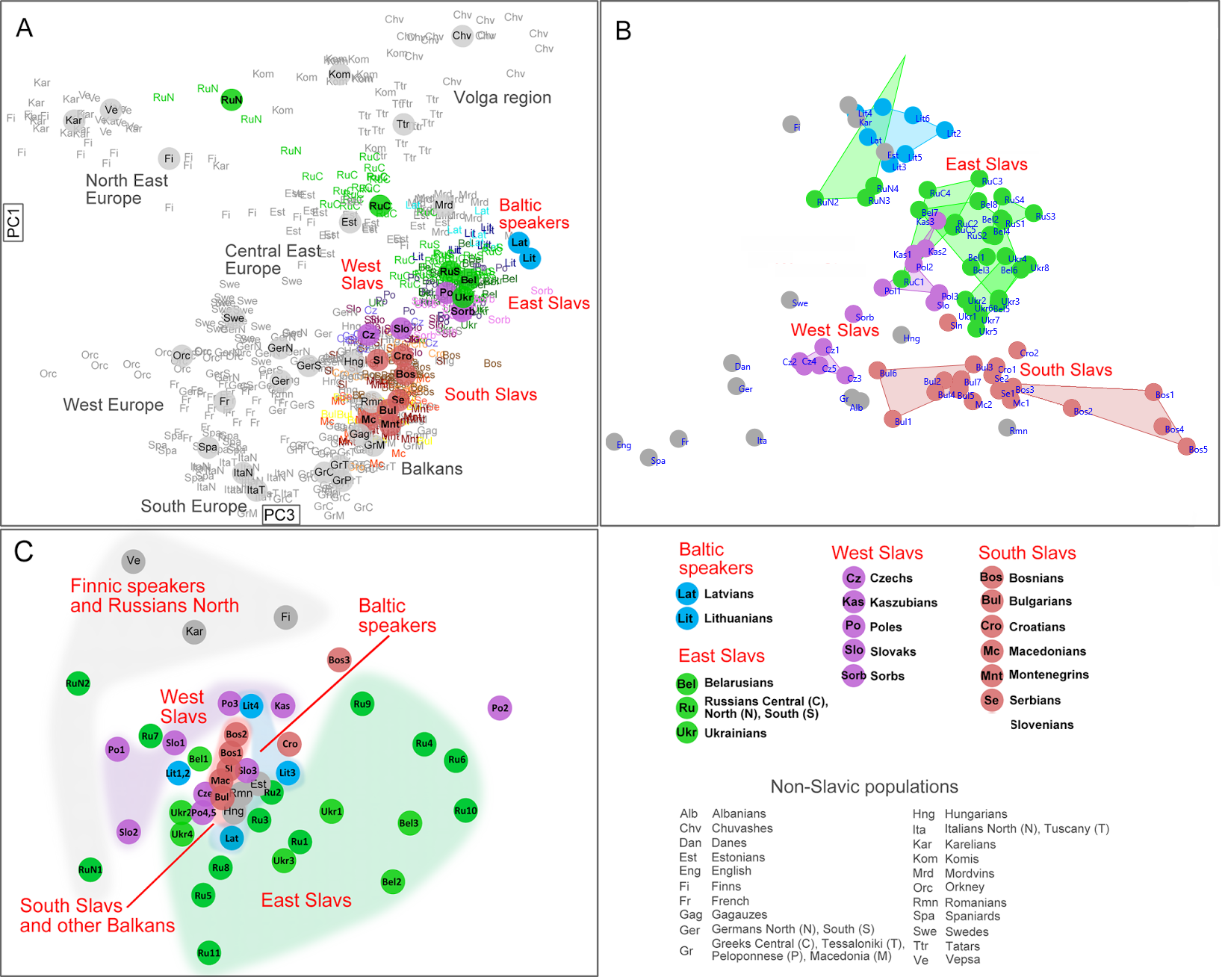

It can be seen on the PCA chart of atDNA that Lithuanians and Latvians are close genetically to Estonians, Belarusians, North Russians, Polish people and Mordvins but still form their own cluster between them, except for Estonians[24]. The Mordvin relation could be explained by the Fatyanovo-Balanovo connection, meaning that Mordvins resemble that Bronze Age population up to this day. The Estonian connection could be explained by the theory presented in the Indo-European Estonia article, that before the Finno-Ugric expansion to Europe around 500 BC it was mostly inhabited by the R1a-M558 Baltic speaking Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer population. Estonian DNA places itself between Latvian and Finnish samples but it still remains much closer to the Latvian cluster[24].

According to one study a modern man with a Lithuanian surname Isdonaitis belongs to Y-DNA haplogroup N-L1025 (found in Russia, Finland and parts of Poland), one person named Aukskalnis belongs to haplogroup N-Y5580, Eidžiūnas and Gudeliauskas belong to N-L551[25]. Nowadays almost 42% of Lithuanians belong to the haplogroup N1 but all clades presented above originated only around 700 BC and they appeared in Lithuania around 500 BC, the population before that era carried mostly subclades of R1a-Z280 (for example R1a-Z92 or R1a-M558). Currently the N1c1 Y-DNA in Balts belongs to the following mutations: L550, L1025, M2782, M2783, M2784. The Gediminids dynasty was also determined to belong to the N1c-L551 haplogroup[26].

In modern Latvia paternal Y-DNA haplogroups R1a and N1a1-Tat are the two most frequent reaching 40% each. R1a of Latvians is predominantly M558 (R1a-CTS1211 from R1a-Z280, brotherly to R1a-Z92, formed around 2400 BC) and compared to other populations also has the highest concentration of M558 among R1a. N1a1-Tat mutation originated in East Asia and had spread through the Urals into Europe where it is currently most common among Finnic, Baltic and Eastern-Slavic peoples. Latvians and Lithuanians have a predominance of the L550 branch of N1a1-Tat. N1c1a was present in 41.5%, R1a-M558 in 35.2% and I1 (M253) in 6.3% of the samples analyzed[27].

Unlike R1a-M458, the R1a-M558 is also common in the Volga-Uralic populations. R1a-M558 occurs at 10% - 33% in parts of Russia, exceeds 26% in Poland and Western Belarus, and varies between 10% and 23% in Ukraine, whereas it drops 10-fold lower in Western Europe. In general, both R1a-M458 and R1a-M558 occur at low but informative frequencies in Balkan populations with known Slavic heritage. The rarity of R1a-M458 and R1a-M558 among Central Asian and South Siberian R1a samples suggests low levels of historic Slavic gene flow[28].

Archaeological findings suggest that Finno-Ugrians had a minor contribution on the Lithuanian population. However, Y-chromosome biallelic markers showed similarities between both Lithuanians and Latvians and the Finno-Ugric Estonians and Mari. On the other hand, while mtDNA diversity also show this connection of Lithuanians to Finno-Ugric speakers, it also revealed similarities with Slavic speaking populations. Finally, analysis of molecular variance using the mtDNA HV1 region and Y STR haplotypes showed that Lithuania is a homogeneous population[29].

Apparently long isolation of the Balts may have contributed to the preservation of an ancient social structure and of archaic language. In addition, the establishment of the Baltic tribes lead to the development of the current Lithuanian dialects, resulting in the actual regional linguistic differentiation. Six dialects can be currently distinguished in Lithuania: three groups from Aukstaitija (West, South and East) and three groups from Zemaitija (North, West and South)[30].

Preserved Baltic traditions

According to the Histories of Herodotus (5th century BC), the Neuri (Νευροί) were a tribe living beyond the Scythian cultivators, one of the nations along the course of the river Hypanis (Bug river), West to the Borysthenes (Dniepr river). This was roughly the area of modern day Belarus and Eastern Poland by the Narew river, coinciding with the Jatvingian (Yotvingian) linguistic territory of toponyms and hydronyms[31].

Ptolemy was the first to mention the Galindians and Sudovians (Koine Greek: Galindoi kai Sudinoi – Γαλίνδοι και Σουδινοί) in the 2nd century AD[32]. Later in history around 14th century AD Peter von Dusburg mentions that the lands of Galindians were finally emptied by the Masovian Christians and then by Jatvingians (Sudovians) and Lithuanians, who took the remaining Galindians into slavery. Before those events he says that Galindian women asked the great local prophetess what should they do to avoid the killings of their daughters by their husbands and so the prophetess said that "The Gods want all men to go and raid the Christian lands", after they came back with lots of goods, the Christian revenge was severe.

The Russian chronicles first mention Eastern Galindians as Goliadj in 1058 AD. Prince Yury Dolgorukiy arranged a campaign against them in 1147 AD, the year of the first mention of Moscow in the Russian chronicles. Subsequent chronicles did not mention the Eastern Galindians anymore.

In Nowe Bagienice (Bartian/Galindian lands), Poland there were 4 kurgans discovered with cremation burials inside from around 500 AD[33]. According to a legend, 6th century AD Prussian king Widewuto ruled wisely and issued laws regulating family life (for example, men could have three wives; burning of gravely sick relatives was allowed; infidelity was punished by death), public life (for example, slavery was prohibited; distinguished warriors with a horse were raised to nobility), and there were punishments for criminal activity. His brother Bruteno was the high priest (Kriwe-Kriwajto) in charge of religious life. Widewuto had twelve sons, whose names were memorialized in the districts of Prussia. For example, Lithuania was named after eldest son Litvas, Sudovia after Sudo. At the age of 116, Widewuto burned himself together with Bruteno in a religious ceremony at the temple of Romuva. After their deaths the brothers were worshipped as god Wurskaito[34].

In 997 AD Adalbert of Prague (Polish: święty Wojciech) was killed by pagan Prussians. Adalbert achieved some success in christianization upon his arrival, however his arrival mostly caused strain upon the local Prussian populations. Partially this was because of the imperious manner with which he preached, but potentially because he preached utilizing a book. The Prussians had oral society where communication was mainly face to face (also according to Dusburg) . To the locals Adalbert reading from a book may have come off as a manifestation of an evil action. He was forced to leave that first village after being struck in the back of the head with an oar by a local chieftain, causing the pages of his book to scatter upon the ground. He and his companions then fled across the river[35].

In the next place, where Adalbert tried to preach, his message was met with the locals banging their sticks upon the ground, calling for death of Adalbert and his companions. Retreating once again Adalbert and his companions went to a marketplace of Truso (near modern-day Elbląg, Poland). Here they were met with a similar response as at the previous place. On 23rd of April 997 AD, after a mass, while Adalbert and his companions lay in the grass while eating a snack, they were set upon by a pagan mob. The mob was led by a man named Sicco, possibly a pagan priest, who delivered the first blow against Adalbert, then the others joined in. They removed Adalbert's head and mounted it on a pole while they returned home. It is recorded that his body was bought back for its weight in gold by King Boleslaus I of Poland[36].

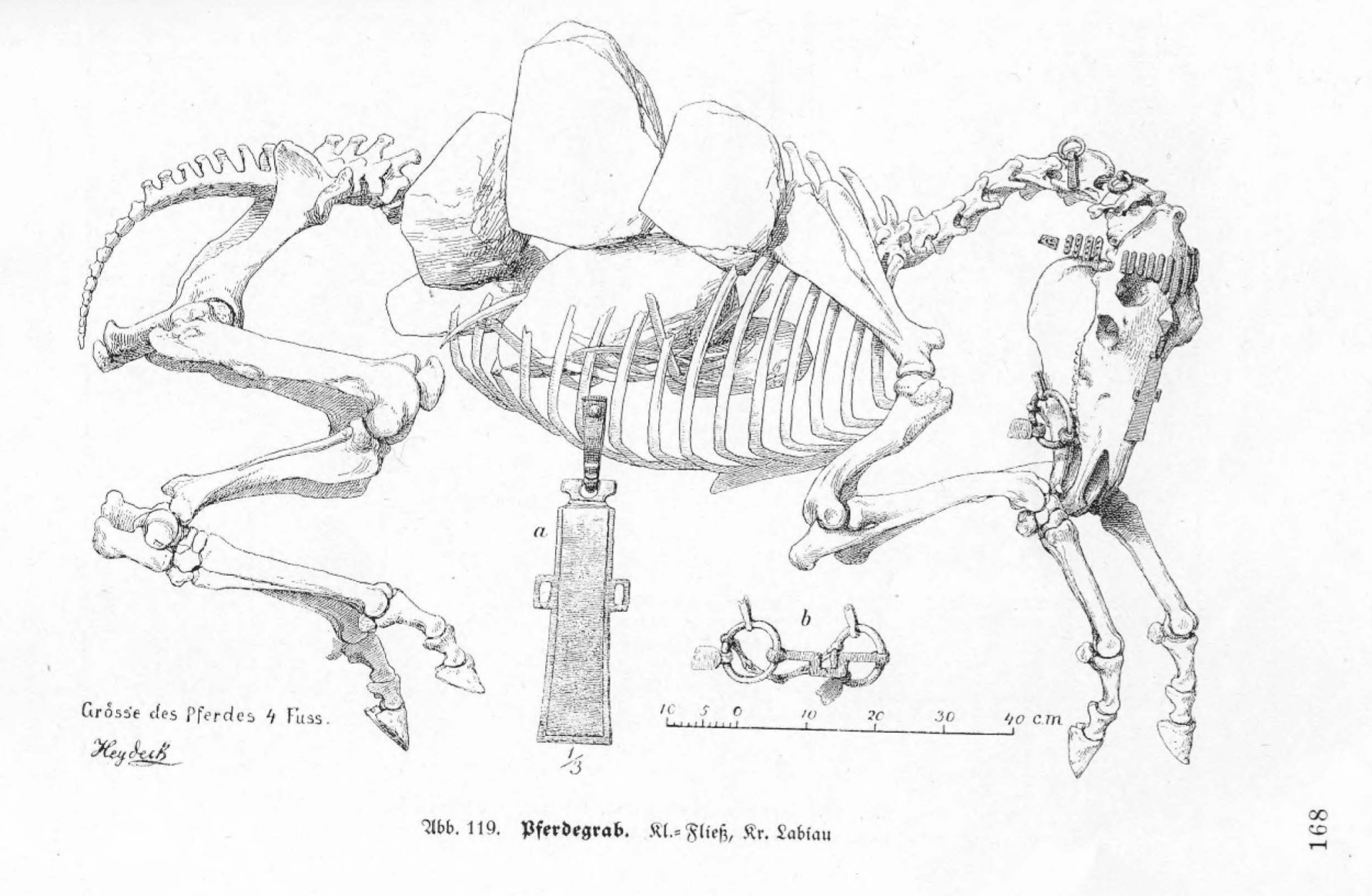

In the Poganowo village near Kętrzyn, Poland there was a sacred grove discovered from around 10th century AD with stone stelae, wooden pillars and 90% of charred horse bones scattered around[37][38].

In 1150 AD Helmold wrote in his chronicle:

The Prussians have not yet learnt the light of faith. However, they are endowed with many good qualities, they are extremely humane towards those who suffer and rush to the aid of those who are in danger at sea, or are persecuted by sea robbers. Gold and silver mean almost nothing to them. They possess many types of furs, which spread the deadly venom of pride over our world. They value them on par with manure, while we, I think, towards our condemnation sigh to those furs as if they were the best thing in the world. For the linen garment, which they call "faldone", they offer us such costly martens (furs).

Much could be said in praise of this nation if only it professed the Christian faith, whose teachers it inhumanly persecutes. It was with them that the noblest Bohemian Bishop Adalbert received the crown of martyrdom. To this day, although they have everything else in common with us, our access to their groves and springs is forbidden, as they think that they become unclean after the approach of Christians. They use horse flesh for food, they also drink the milk and blood of horses, so that, as they say, they even get drunk on them. The people there have blue eyes, red complexion and long hair. Besides, they are inaccessible because of the mud, and they do not tolerate any master among them.

The Namejs ring is a traditional Latvian ring which represents Latvian independence, friendship and trust, and symbolizes the unity of three ancient Latvian lands - Kurzeme, Latgale and Vidzeme. The design and customs associated with it originated in ancient Latgalian lands, which is the Easternmost of the four historical regions of Latvia. The ring, as currently known, was first produced in the 12th century AD.

Daugirutis or Dangerutis (Dangeruthe or Daugeruthe) was an early Lithuanian duke and he is the second (after Svelgates/Žvelgaitis who died in 1205 AD) Lithuanian duke whose name is known from reliable sources. His life is recorded in the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia; even though no other sources mention his name, he is considered to be one of the most influential pre-Mindaugas Lithuanian nobles. Daugirutis attacked Latvian and Estonian lands many times. His daughter was married to Visvaldis, duke of Jersika (in the present-day Līvāni municipality, Latvia). This marriage protected Latgalian Visvaldis from attacks of Lithuanians, but he had to provide food and shelter for the troops of Daugirutis on their expeditions to plunder the Estonian or Russian lands[39].

In 1213 AD, Daugirutis traveled to Velikiy Novgorod to sign a peace treaty with Mstislav. The chronicles of Novgorod do not mention the treaty. While the purpose of the agreement is not explicitly mentioned, historians assume it was directed against the Livonian Order. On his way back Daugirutis was attacked and captured by the Livonian Order. He was imprisoned in the Cēsis Castle and a large ransom was requested for his release. When his friends arrived to discuss the terms of release, but did not bring enough money for the ransom, Daugirutis killed himself[39].

The following Prussian leaders fought against the German Teutonic Knights in the 13th century AD: Auctume (Auktum, Auttum) and Bart of the Pogesanians; Diwanus (Diwan), Numo, Dersko of the Bartians; Glappo and Pyopso of the Warmians; Herkus Monte of the Natangians; Glande, Sklodo (Ausklode), Nalub, Wargulle of the Sambians; Skomand (Komat), Kudare, Jodute, Skardo of the Sudovians; Stimegota, Sarecka (Sareikā) of the Skalovians (Šalvians, Šalauians). Other notable Baltic leaders were Vīkints and Treniota of the Samogitians; Surmin, Nodam, Sudarg, Mansto, Sesbuto, Živinbudas, Traidenis, Pukuwer and Vytenis of the Lithuanians; Nameisis of the Semigallians; Visvaldis (Vissewalde) of the Latgalians (Jersika); Lammekinus of the Curonians.

Peter von Dusburg claimed in 14th century AD that Prussians worshipped The Sun, The Moon, The Stars, The Lightning and Thunder, birds, insects, 4 legged animals and toads. They had special holy groves, where they never cut down any tress but also holy ponds where they never fished. According to him they also had the highest priest called Krive, who lived in Romove (Romowe) in Nadrovia. Prussians believed in an immortal soul, which after death reincarnated itself into other beings including trees and animals (same as in Hinduism). Some Prussians took baths and other never took them. The women used linen and men used wool to make clothes. The wives had to be bought out for a certain price from their fathers. Dusburg also noted that for Prussians hospitality is very important and all guests had to be served with many dishes. They mostly drink water, mead or mare's milk. They don't care about wealth, they don't care about good clothes, they throw straws on the ground to predict the future.

In 1546 AD Jan Sandecki Malecki claimed that Prussians would pray to Potrimpo, pour hot wax into water, and predict the future based on the shapes of wax figures. Maciej Stryjkowski wrote that there was a copper idol (a twisted žaltys - snake) dedicated to Potrimpo in the temple of Romuva. Simonas Daukantas described Potrimpo as a god of spring, happiness, abundance, cattle and grain.

The Sudovians (Jatvingians) from Prussia believed in the following gods in 1545 AD:

- Okkopirmus (Ockopirmus, like Finnish Ukko) - chief God of Sky

- Parkuns (Perkons, Percunis) - God of Thunder

- Pekols (Peckols) - God of Cattle and Underworld

- Swāikstiks (Swayxtix) - God of Light and Stars

- Autrimpus - God of Sea

- Potrimpus (Natrimpe) - God of Running Water (Rivers)

- Bardoayts - God of Boats

- Pergrubrius - God of Plants

- Pilnitis - God of Abundance

- Pokols (Pockols) - flying spirit or devil

- Puskaits (Puschkayts) - God of Earth

- Barstucke and Markopole - little people similar to dwarves or trolls[40]

Švaikstiks was also known as Suaxtix, Swayxtix, Schwaytestix and among Lithuanians as Žvaigždikis (Žvaigždystis, Žvaigždukas, Švaistikas). The Centum Slavic version of his root name could then be "Gviazdiks" with "G" to "Ž" and "K" to "Š" correspondence (X is equivalent to Satem-Centum combined GŽ and KŠ). His West Slavic Kashubian version is most probably Gwiôzdór[41] and his East Slavic version is Svarog (Sanskrit स्वर्ग - Svarga meaning Heaven[42]). The closest cognates to his name are Old Prussian "swāigstan", Lithuanian "šviesa", Polish "świecić", "światło" all meaning "light".

All Prussians practiced cremation, which was also noted by Wulfstan in 890 AD. The Sambians burned all things with its owner, including swords, armor, horses, clothes, ornaments. The dead had to be celebreated for some days after the burial of ashes (usually in urn)[43].

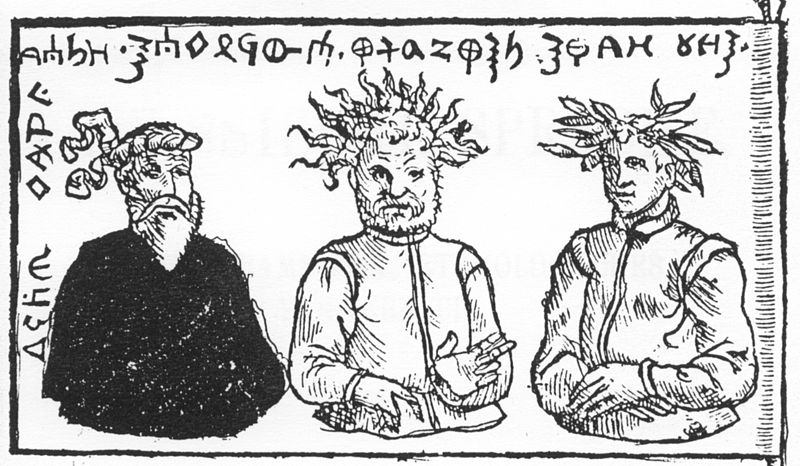

The 1262 AD Tale of Sovius describes the establishing of cremation custom which was common among Lithuanians and other Baltic nations. The names of the Baltic gods Andaius/Andaeva (contemporary to Vedic Varuna and Prussian Patrimps, probably Veles and Triglav as well), Perkūnas (God of Thunder, Diverikzos, Diviriksas, King of Gods), Žvorūna (Goddess of Animals), and a smith-god Teliavelis (Telęvelis, who struck the Sun and threw it into the sky) are mentioned[44]. Similar gods are mentioned in the Hypatian Codex from 1258 AD. In Mordvin and Erzya mythology there is a God of Fire called Tolava, God of Thunder called Purginepaz and the winds are called varma (That is why Prussian "Varmia" could also be translated as "the Land of Winds" next to more common "the Red Land" or "the Worm Land")[45].

"Oh what a great and devilish delusion he brought to the Lithuanians and Yatvingians and Prusssians and Estonians and Livonians and to many other nations who call themselves the Sovici believing that Soviia was a guide for their souls to reach the underworld. And he lived during the times of Abimelech and they until this day bury their dead bodies on funeral pyres much as Achilles and Eant and other such Hellenes"[46].

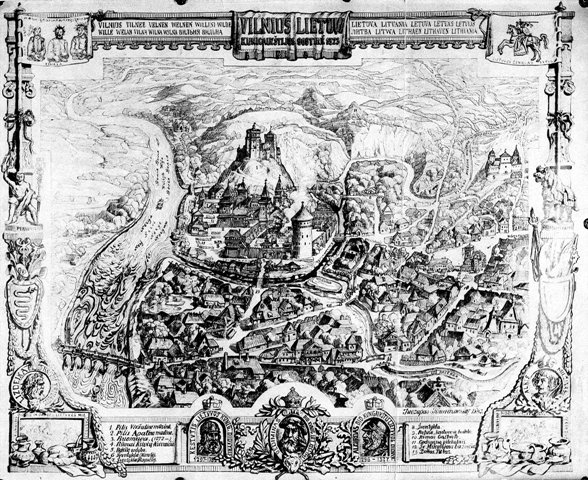

Lithuanian pagan ruler Gediminas died in 1341 AD. He was cremated as part of a fully pagan ceremony in 1342 AD, which included a human sacrifice of his favourite servant and several German slaves being burned on the pyre with his corpse, most probably in Vilnius.

In 1382 AD Kęstutis, son of Gediminas, was found dead by Skirgal. Jagal (Jagiełło) claimed that he hanged himself but few believed him. Jagal then organized a large pagan funeral for his uncle Kęstutis: his body was burned with horses, weapons and other treasures in Vilnius (presumably in Šventaragis' Valley). Earlier in 1377 AD Kęstutis' brother - Algirdas after his death was burned on a ceremonial pyre with 18 horses and many of his possessions in a forest near Maišiagala, probably in the Kukaveitis forest shrine.

As a side note... based on medieval documents I reconstructed true pagan names of all sons of Algirdas and those were: Minigal, Skirgal/Skirgel, Jagal/Jagalis (Jagieł/Jagiełło), Korigal, Swidrigal, Koribut, Lingwen/Lugven, Wingunt. Later forms of those names ending with -iełło and -ło are russifications of male names in neutrum form, which should end with -is or -as in proper Lithuanian male form. For example the other name of Lithuanian boyar Kinsgal (Keżgal) is always written in documents without -ło opposite to its modern Polish form Kieżgajło, similar case is with surname Sunigal/Songal and Sunigajło (but here the Sungaylo form is in evidence). Other evidence is that -la or -lla was reserved for female names such as Ryngałła or Ringaila, Aldona (sisters of Algirdas) also disproving all "Skirgaila" or "Jogaila" malformed reconstructions of modern Lithuanian historiography (those are female form names of male dukes), which are itself lithuanizations of russified forms with wrong -lo turned to -la. Those forms came into existence because the official language of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the 15th century AD was the Ruthenian language (not Russian/Moscovite), which preferred the -ło ending of male names.

The so-called Elbing Vocabulary, which consists of 802 thematically sorted Old Prussian words and their German equivalents was copied by Peter Holcwesscher from Marienburg around 1400 AD. Some Prussian words are more similar to Polish when compared to Lithuanian, for example (EN -- PR - PL - LT):

grain -- zirne - ziarno - grūdai; bag -- torbis - torba - maišas; beer -- pewo - piwo - alus; eagle -- arelie - orzeł (or'el) - erelis; beaver -- bebrus - bóbr - bebras; european bison -- zambrs - żubr - stumbras; iron -- gelso - żelazo - geležis; donkey -- asilis - osioł - asilas; poppy -- moke - mak - aguonos; plow -- plugis - pług - plūgas; chair -- kreslan - krzesło (kreslo) - kėdė; moustache -- wanso - wąs (wans) - ūsas; brain -- muzgen - mózg - smegenys; Friday -- pentinks - piątek - penktadienis; daughter -- docki - doćka (córka) - dukra; helm -- chelmo - chełm - šalmas; draught -- sauson - susza - sausra; water -- wunda - woda - vanduo; people -- ludis - ludzie - žmones; ass - peisda - pizda - šiknius;

There is also a full Prussian sentence written down in 1369 AD:

Prussian: Kayle rekyse thoneaw labonache thewelyse Eg koyte poyte nykoyte penega doyte[48]

Polish: Hej rycerzu ty nie jesteś dobrym wujaszkiem, Jak chcesz pić, jeśli nie chcesz pieniądza dać

Lithuanian: Ei riteri, tu nesi geras dėdė, Kaip tu nori gerti jei nenori pinigų duoti

Latvian: Kungs, jūs vairs neesat labs tēvocis, Kopš jūs vēlaties dzert, bet nevēlaties naudu dot[49]

English: Hello lord, you are no longer a good uncle, How do you want to drink if you do not want coin to give

There is a visible exchange of "K" to softer "H" as "CH" or even "KH" in Slavic, "TE" to "Ć", and "G" to Polish "DZ" in part of this sentence and when it is linguistically transformed it is much easier to spot this:

Eg koiti poiti nikoiti penega doiti

Eg chojte (khoite) pojte nichojte (nikhoite) penega dojte

Jeg chocze (choči, xotěti) poić (poiti) nichocze (nichoči) pieniega doić (daiti)

The Prussians were extremely reluctant to accept the new religion, and for practicing pagan festivals in the groves, sacrificing animals and ceremonially washing off Christian baptism from children, they brought upon themselves the wrath of the Bishop of Sambia even around 1430 AD[50].

The lands of Samogitia (Žemaitėjė) were christianized only in 1413 AD (Lithuania was in 1387 AD)[51]. During the same year it was noted that eternal Holy Fire still burns near Nevėžis river and it had to be put down. Another eternal fire was kept by pagan priests near Dubissa river. In 1418 AD the Samogitians rebelled against Vytautas and christianization, opting for Swidrigal (Świdrygiełło) but Kinsgal (Kieżgajło Wolimuntowicz) in 1419 AD bloodily suppressed the Samogitians, beheading 60 of their most important leaders.

According to the 15th century AD Polish chronicler Jan Długosz (born in 1418 AD), the Lithuanians, Samogitians and Jatvingians (Yotvingnians) were the same people, who spoke the same language and all of them kept the eternal Holy Fire in their most important forts. According to him they praised snakes and saw the God of Medicine (Asclepius) in those creatures, he wrote that most of Lithuanians kept a snake in their house and fed it milk. The hens (male chickens) were also sacrificed as offerings to those snakes. Długosz name for the Lithuanian Thunder God was "Perkun" and he translated it as "Thunderer". He pointed out that only very special forests and some rivers or ponds were made into holy groves, while the rest could be used for gathering wood or fishing freely.

Nowadays Lithuania (Lietuva) consists of lands previously inhabited by different Baltic tribes such as: Selonians around Rokiškis and Biržai, Semigallians around Joniškis in the North, Curonians[52] around Plungė and Palanga, Samogitians around Šiauliai, Lithuanians around Vilnius, Varėna, Kaunas, Utena, Jatvingians (Yotvingians, Dainava) around Alytus, Kazlų Rūda and Mariampolė. There are attested names of Curonian noblemen such as: Lammekinus, Veltūnas, Reiginas, Tvertikis, Saveidis. Samogitian words such as kuisis (mosquito), pylė (duck), blezdinga (swallow), cyrulis (skylark), zuikis (rabbit), kūlis (stone), purvs (marsh), and pūrai (winter wheat) are considered to be of Curonian origin[53].

Modern bands such as Romowe Rikoito, Obtest, Skyforger[54], Kūlgrinda[55], Romuvos, Poccolus, Zpoan Vtenz, Žalvarinis, Ugniavijas and organizations like Pruthenia, Romuva[56] and Latvijas Dievturi preserve the forgotten pagan Baltic traditions until this day. There is even a pagan temple in Latvia named Lokstene Shrine of Dievturi. In Lithuania some pagan celebrations take place during Mėnuo Juodaragis[57] and Kilkim Žaibu festivals and in Latvia during Zobens un Lemess festival.

Interesting article by Marija Gimbutas on the Bronze Age in the Baltics.

Much appreciation goes to the scientific works of Marija Gimbutas, Mirosław Hoffmann, Elena Grigalavičienė, Baiba Vaska and many other archaeologists and historians, who spent their lives investiagting the region of Eastern Baltic area.

Article created between 5th of January 2022 and 28th of February 2022. First published on the 4th of March 2022. Updated on 11th of Novemeber 2022 with DNA samples from pre-3000 BC Lithuania and Latvia.