Indo-European Estonia

Estonia is a country situated in Northern Europe and its citizens speak a unique language that does not belong to the Indo-European language family but instead it is a Finno-Ugric language, nevertheless there are many words in the Finnic branch of those languages that are in common with the Indo-European languages and most probably those words were already used by the people of the Corded Ware Culture.

Nowadays most of Estonians have blond hair, light eyes and are quite tall when compared to other Europeans or people from Asia. From the Middle Ages their culture was heavily influenced by the Germanic Danes, Swedes and Germans from the Teutonic Order, there was also some influence coming from the Polish culture (for example Stephen Bathory gave Tartu its red-white flag). In the 18th century Estonia was incorporated into the Russian Empire, in the beginning of 19th century Finland became part of the Tsardom aswell. Both countries became indepenedent again at the beginning of the 20th century (1917 AD and 1918 AD).

The origin of Estonians begins with the first settlers of Europe, the Neanderthals. Just like other Europeans the Estonians share around 3% - 5% of their autosomal DNA with this very ancient group of Humans that appeared in Europe for the first time around 400000 BC and were still present in some areas of Finland around 120000 BC before the latest Ice Age occured.

The Ice Age

The earliest recorded Human (Homo Sapiens) presence in Estonia is a small settlement of Kunda Culture near the modern village Pulli dated to 9000 BC. It is two kilometers from the town Sindi, which is situated 14 kilometers from Pärnu. A dog's tooth found at the Pulli settlement is the first evidence for the domestication of this animal in the territory of Estonia.

People who lived at Pulli probably moved there from the South after the ice cap had melted in Estonia, moving along the Daugava river in Latvia, then along the Latvian-Estonian coast of the Baltic Sea, and finally to the mouth of the Pärnu river. There are not many natural sources of flint in the territory of Estonia. However, black flint of high quality from Southern Lithuania and Belarus is identical with examples found at the Pulli settlement.

In 2017 Jones et al. determined that peoples of the Kunda Culture and the succeeding Narva Culture showed closer genetic affinity with Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG) than with Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHG)[1]. It also means that most probably they carried the Y-DNA I1 haplogroup rather than R1a or R1. In 2018 Mittnik et al. analyzed the remains of a male and female ascribed to the Kunda Culture. They found that one male carried a Y-DNA haplogroup I and mtDNA U5b2c1, while one female carried mtDNA U4a2. They were found to have "a very close affinity" with Western Hunter-Gatherers, although with "a significant contribution" from Ancient North Eurasians (ANE). U5b2c1 is considered to be one of the most ancient haplogroups in Europe. It is remarkably rare in modern populations today, found in Europe at levels of less than 1%[2].

U4 is found in the endangered Nganasan people of the Taymyr Peninsula, in the Mansi (16.3%), and in the Ket people (28.9%) of the Yenisei River in Siberia. It is found in Europe with highest concentrations in Scandinavia and the Baltic states, and is found in the Saami population of the Scandinavian peninsula (although, U5b has a higher representation there). U4 is also preserved in the Kalash people (current population size: 3700) a unique tribe among the Indo-Aryan peoples of Pakistan where U4 (subclade U4a1) attains its highest frequency of 34%[3].

The ANE ancestry of Kunda Culture people was lower than that of Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers, indicating that ANE ancestry entered Scandinavia without traversing the Baltic. In 2018 Matthieson et al. analyzed a large number of individuals buried at the Zvejnieki burial ground in Latvia (5500 BC), most of whom were affiliated with the Kunda Culture and the succeeding Narva Culture. Their mtDNA belonged to haplotypes U5, U4 and U2, the vast majority of the Y-DNA samples belonged to R1b1a1a and I2a1[4]. The results affirmed that the Kunda and Narva cultures were about 70% WHG and 30% EHG. The detected ANE ancestry of the Kunda Culture came most probably from this Eastern Hunter-Gatherer admixture.

The nearby contemporary Pit–Comb Ware Culture was on the contrary found to be about 65% EHG. Around 3700 BC there was a complete turnover to Y-DNA R1a1a1, from 500 BC onward mainly in Estonia with increasing impact of Y-DNA N1 (Mittnik 2018, Saag 2019, and others).

All those genetic results could point to the fact that the Estonian language and most probably the Finnish language could still carry substratum words from Ancient North Eurasians that are in common with words that can be found in the Native languages of the Americas:

- heart: süda, sydän, sidām, südäin

- Kamassian (Samoyedic Russia above Mongolia): sī

- Tundra Nenets: сей (siey)

- Erzya: седей (sedej)

- Enets (Siberia): сео (tseo)

- Hindi: गूदा (gūdā)

- magpie (pica pica): harakas, harakka

- Tundra Nenets: хӑрна (harna, χərnā)

- Alutiiq (Central Alaskan): qallqayaq (kalkaiak, maybe from *sarkaiak)

- Proto-Norse: ᚺᚨᚱᚨᛒᚨᚾᚨᛉ (harabanaz)

- Slovincian: sãrka

- Lithuanian: šarka

- Old Prussian: sarke

- Belarusian: саро́ка (saróka)

- thin: lahja, laiha

- Hawaiian: lahi

- Lithuanian: liesas

- Occitan: linge

This word might be of ANE, Neanderthal or Denisovan origin

- grey: harmaa, harmaja, harmava, harmai, harmag

- Japanese: 灰色 (はいいろ, hai-iro)

- Old English: hār

- Old Norse: hárr

- Pashto: خړ (hëṛ)

- Urdu: سرمئی (surmaī)

- Latvian: sirms

- Malayalam: ചാരം (sāraṃ)

- Chuvash: сӑрӑ (sără)

- Hindi: धूसर (dhūsar) ("smoke grey")

- Kazakh: сұр (sur)

- Lower Sorbian: šery

- Belarusian: шэ́ры (šéry)

- Tatar: соры (sorı)

- pig, boar: siga, sika, šiga, tsiga, metssiga ("forest-pig")

- Cherokee: ᏏᏆ (siqua)

- Polish: dzik (tsig) ("boar")

- Catalan: senglar (maybe from *singlar, *siglar)

- Occitan: singlar

- Hindi: जंगली सूअर (jaṅglī sūar, dzankli suar) ("forest-pig")

- Latvian: mežacūka ("forest-pig")

- Russian: ди́кая свинья́ (díkaja svinʹjá)

There are not many words like that and more of those appear in the Indo-European languages and the Native American Navajo language, which would mean that ANE had more impact on the Eastern Hunter-Gatherer population (R1 Y-DNA). For example a word connected to all R1 language groups is a name for someone OLD.

Farmers Go Away!

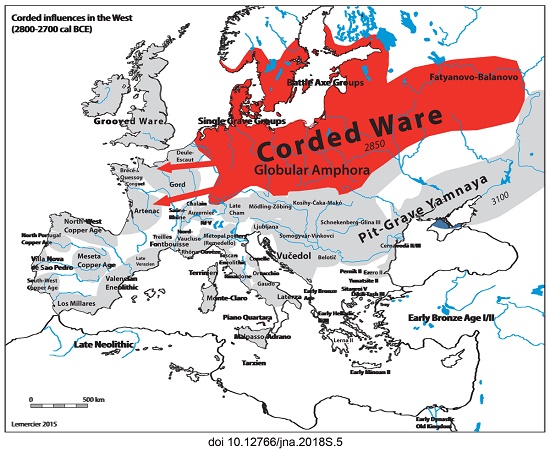

2017 study by Jones et al. found no evidence of Early European Farmer (EEF from Anatolia) admixture among Neolithic populations of the Eastern Baltic and the East European Forest-Steppe, suggesting that the Hunter-Gatherers of these regions avoided genetic replacement while adopting Neolithic cultural traditions like farming. A 2017 Saag et al. study found that the people of the subsequent Corded Ware Culture in the Eastern Baltic carried Yamna and Hunter-Gatherer related paternal and autosomal ancestry, and some Early European Farmer (EEF) maternal ancestry.

Corded Ware Culture

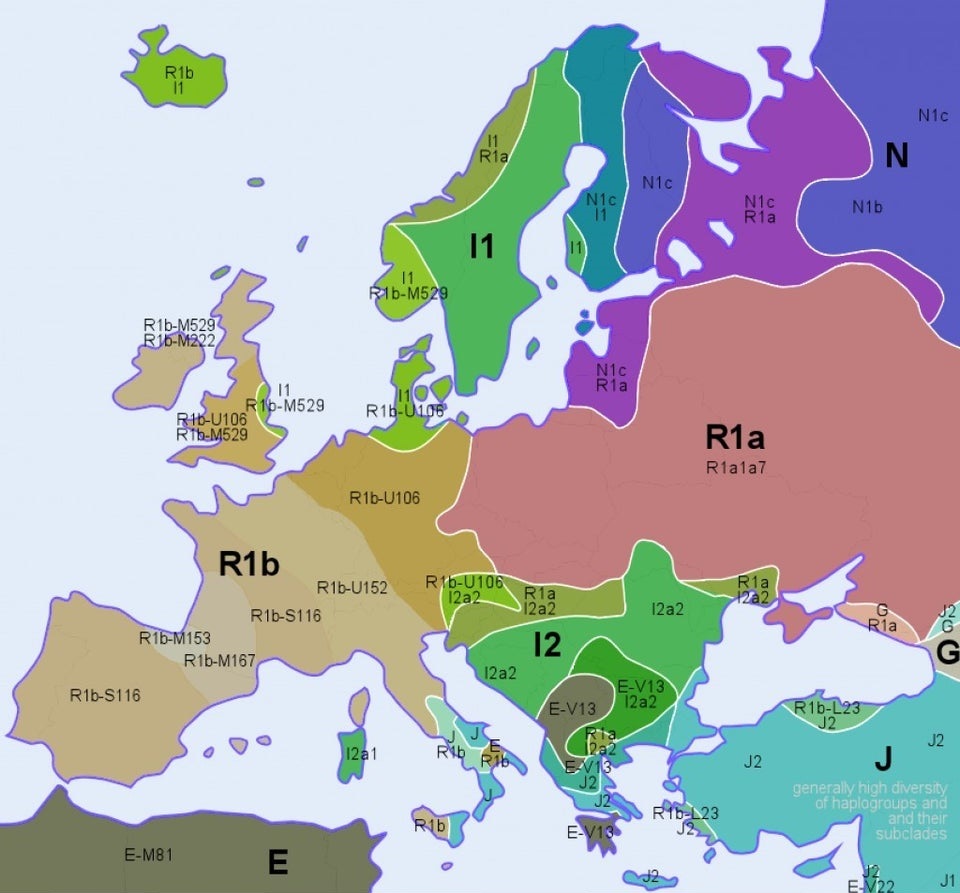

The 3600 BC Kudruküla (Eastern Estonia) Comb Ceramic Culture (CCC) Hunter-Gatherer sample was assigned to Y-DNA haplogroup R1a5 as it was called with derived alleles in two R1a-M420 and one R1a5-YP1272 defining site. The data supports the assignment of Kudruküla into an early offshoot R1a5 branch of haplogroup R1a. This finding is further supported by the report of similar cases of R1a lineages which are derived at M459 but ancestral at M198 SNPs in two Eastern Hunter-Gatherer genomes, one from Karelia and the other from near Samara. Altogether, these findings suggest that various subclades of R1a may have been common in Hunter-Gatherer populations of Eastern Europe and that just one of them, R1a-M417, was later amplified to high frequency by the Late Neolithic/Bronze Age expansion.

The fact that two Latvian Hunter-Gatherer Y-DNA haplogroups have been characterized as belonging to R1b-M269 clade suggests that both sub-clades of R1 were present in the Baltic area before the expansion of the Corded Ware Culture. All four of the Estonian Corded Ware Culture individuals could be assigned to the R1a-Z645 subclade of haplogroup R1a-M417 which together with N is one of the most common Y chromosome haplogroups in present-day Estonians at 33% of male population. Importantly this R1a lineage is only distantly related to the R1a5 lineage found in the Comb Ceramic Culture (CCC) sample.

The finding of high frequency of R1a-M417 in Estonian Corded Ware Culture samples is consistent with the observations made for other Corded Ware sites that along with Late Bronze Age remains associated with Sintashta Culture also show high frequency of haplogroup R1a-M417. However the remains associated with the Yamnaya Culture, which is considered to be ancestral to Corded Ware Culture, have been found with predominantly R1b-Z2105 and no R1a lineages. On the other hand, no such clear differentiation was revealed when comparing the mtDNA haplogroup composition of the remains associated with the respective cultures.

Estonian Comb Ceramic Culture (CCC) samples positioned between Scandinavian and Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (SHG and EHG) quite far from Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG). Since the Mesolithic Hunter-Gatherer individuals from the Baltics have been shown to cluster with WHG, this could point towards genetic input from the East. The Estonian Corded Ware Culture individuals on the other hand clustered closely together with a bulk of modern as well as Late Neolithic/Bronze Age (LNBA) populations from Europe. Estonian Hunter-Gatherers of Comb Ceramic Culture are closest to Eastern Hunter-Gatherers.

The Estonian first farmers of Corded Ware Culture show high similarity in their autosomal DNA with Steppe Belt Late Neolithic/Bronze Age individuals, Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers and Iranian Farmers while their X chromosomes are most closely related with the European Early Farmers of Anatolian descent. These findings suggest that the shift to intensive cultivation and animal husbandry in Estonia was triggered by the arrival of new people with predominantly Steppe ancestry (Corded Ware Culture), but whose ancestors had undergone sex specific admixture with Early Farmers with Anatolian ancestry[5].

The beginning of the Late Neolithic Period in Estonia is characterized by the appearance of the Corded Ware Culture pottery with corded decoration and well-polished stone axes. Evidence of agriculture is provided by charred grains of wheat on the wall of a corded-ware vessel found in Iru settlement. Osteological (bone) analysis show an attempt was made to domesticate the wild boar. Specific burial customs were characterized by the dead being laid on their sides with their knees pressed against their breast, one hand under the head. Objects placed into the graves were made of the bones of domesticated animals.

Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture

A similar situation occured with the movement of people associated with the R1a-Z93 Y-DNA haplogroup from the region of Carpathian Mountains and Western Ukraine towards the Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture. Those people would later form the Sintashta Culture and become the ancestors of Indo-Aryans (modern Persians and Hindus). This would suggest that some common Indo-Aryan and Indo-European Estonian myths would go back as far as 3500 BC. One of those myths could be the Vedic myth of Vala stealing the sacred cows and Finnish myth of Wellamo, whose magical cows feed on the sea hay.

The Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture was the Easternmost group of the Corded Ware Culture and occupied the centre of the Russian Plain, from Lake Ilmen and the Upper Dnieper drainage to the Wiatka river and the middle course of the Volga. From the few available dates, the oldest ones from the plains of the Moskva river, and from the late Volosovo Culture containing also Fatyanovo materials, and in combination they show a date of circa 2700 BC for its appearance in the region. The Volosovo Culture of foragers eventually disappeared when the Fatyanovo Culture expanded into the Upper and Middle Volga basin.

There is a clear interaction sphere between the Eastern Gulf of Finland area reaching from Estonia to the areas of Finland and the Karelian Isthmus in Russia. Evidenced by the sharp-butted axes derived from the Estonian Karlova axe and Y-DNA haplogroup R1a-Z282 in Finland (related to the Indo-Aryan R1a-Z93).

Gallery Of Artifacts

Indo-European Words in Estonian and Finnish

- seven: seitse, seitsemän, seitsen, säidse, seiččemen, seičeme (maybe from *seidem)

- Kashubian: sétmë

- Middle Welsh: seith

- Cornish: seyth

- Breton: seizh

- Italian: sette

- Polish: siedem

- Old Hindi: सात (sāta)

- Latvian: septiņi

- Ancient Greek: ἑπτά (heptá)

- Romanian: șapte

- Tocharian A: ṣpät

- Sanskrit: सप्तन् (saptán)

This word appears only in the European branches of Finno-Ugric. It could even be associated with the Western European Hunter-Gatherers because the straight connection is formed mostly with Welsh and other P-Celtic languages. The "th" would then originate in "ts" or the opposite way: from seith to seits; "ts" easily transforms to "č" and it is often used to transcribe Slavic "c" too (as "ts"). The "ts" could also come from the hardened "d" because in a smiliar Finnic word "metsä" the Indo-European cognates mostly have "dz" or "di" instead of "ts". If that is the truth then the closest would be the Slavic "seidemän", "seiden", which would correspond to Slovak "sedem", Bulgarian "седем (sedem)" and Polish "siedem".

Maybe the most logical explanation would be the transformation: from "sept" to "sebt" (from here to "sev" and "sef" only in Germanic R1a-Z284), then with dropped "b" to "set", then hardened to "sed" or softened to "seč". The closest relative to Finnish "seitsemän" is the Kashubian "sétmë", which proves that both could come from either R1a-Z282 or even earlier R1a-M558. It is not necessarily the Indo-Aryan (R1a-Z93) loanword in Finno-Ugric.

Another word would be Estonian "valitsus" literally translated to Polish "władza" (*walidzus), Lithuanian "valdžia" and Latvian "valdība", which would render the original R1a-M558 word as "valdzus" or "val'dz'us" common also among the R1a-Z282 and R1a-M458 tribes. The Sanskrit "राज्य (rājya, radžia)" in R1a-Z93, Old Norse "landreki" in R1a-Z284 and "𐌓𐌄𐌗 (rex)" in Latin and Faliscan suggest that in the times of R1a-M417 and R1a-Z645 around 3500 BC or 4000 BC there were still two names for the "ruling power". This second name might be connected to a Polish (R1a-M458) words "rząd" (*rands) and "rada", and Belarusian word "ура́д (urád)".

R1a-M458 and R1a-M558 have similar distributions, with the highest frequencies observed in Central and Eastern Europe. R1a-M458 exceeds 20% in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland and Western Belarus. This lineage averages from 11% to 15% across Russia and Ukraine and occurs at 7% or less elsewhere. Unlike R1a-M458, the R1a-M558 clade is also common in the Volga-Uralic populations. R1a-M558 occurs from 10% to 33% in parts of Russia, exceeds 26% in Poland and Western Belarus, and varies between 10% and 23% in Ukraine, whereas it drops 10-fold lower in Western Europe.

In general, both R1a-M458 and R1a-M558 occur at low but informative frequencies in Balkan populations with known Slavic heritage. The clustering of European populations is due to their high frequencies of R1a-M558, R1a-M458, and R1a-Z282*, whereas the R1a-M780 and R1a-Z2125* lineages account for the South Asian (Indo-Aryan) character of the other extreme. In Estonia R1a-M558 occurs in 20% of all R1a samples, in Latvia in 25% and in Slovenia in 30%![6].

- kurgan, heap, barrow, mound: kääbas

- Lithuanian: kapas ("grave"), kapinės ("cemetery")

- Latvian: kaps ("grave")

- Polish: kopiec (maybe from earlier *kopes) ("kurgan, barrow, mound")

- Latgalian: kops ("grave")

- Persian: کپه (koppe) ("pile")

- Old Saxon: hōp

- Old Norse: hópr (from earlier *kops)

- Russian: ки́па (kípa) ("pile")

- Polish: kupa ("pile")

- Latgalian: guba ("pile", same as kupa)

- German: Haufen (from *kaupen) ("pile")

- English: heap (from *keap) ("pile")

In Estonia the kurgan burials disappeared only in the 15th century AD. The other name for a barrow or a tomb in Estonian is "kalme", similar to Hungarian "halom".

- saddle: satula, sadul

- Latvian: sēdeklis, sedulka

- Old Saxon: sadul

- Old Norse: sǫðull

- Polabian: sedlu

- Albanian: shalë

- Aromanian: shauã

- Belarusian: сядло́ (sjadló)

- Latin: sella

- woods, forest: mets, metsä, mettsä, meččä, meččy, mečč, mec

- Lithuanian: mẽdžias

- Polish: miedza ("balk, border")

- Latvian: mežs

- Old Prussian: median

- Lithuanian: mẽdis ("tree")

- Russian: межа́ (mežá) ("border between the field and a forest; a small forest"

- Old Church Slavonic: межда (mežda)

- Ancient Greek: μέσος (mésos) ("middle, between")

This word appears only in the Finnic languages so it must be an Indo-European substratum word in Uralic languages. If the proto form of this word in the Finnic languages was "*medsa" then the Lithuanian "mẽdžias" would be its closest relative but also the Polish "miedza". The Sanskrit word for middle: "मध्य (mádhya)" would then come from "*madsia".

- boat: lootsik

- Old Polish: loodz

- Polish: łódź, łódka

- Old East Slavic: лодья (lodĭja)

- Russian: ло́дка (lódka)

- *Santali: ᱞᱟᱹᱣᱠᱟᱹ (lăvkă)

- Albanian: lundër

In Inari Sami language it is "käärbis" and in North Sami "gárbbis", which are cognates to Polish "korab" and Ancient Greek "καράβι (karabi)". Again it is a word related to I1 and I2 tribes.

- brush: pintsel

- Polish: pędzel

- Old Armenian: փունջ (pʿunǰ)

- German: Pensel

There is a certain nasal vowel "in", "en" and "un" in this word, also "dz" is kept in all cognates. This might not be a cognate but it shows clear relation of Estonian "ts" to "dz".

- tasty: maitsev, magus, maukas, makoisa

- Bikol Central (Philiphines): masiram

- Korean: 맛있다 (masitda)

- Urdu: مزیدار (mazedār)

- Polish: smakowity

- ram: oinas

- Ancient Greek: οἶς (oîs)

- Old Irish: oí

- German Low German: Öi

- Dutch: ooi

This word might be of I1a (Western and Scandinavian) or I2a (Central and South) Hunter-Gatherer origin.

- wax: vaha (maybe from *vaska)

- Latvian: vasks

- Polish: wosk

In the Volga-Permic languages it is for example in Udmurt: "śuś" and in Komi: "śiś", so it did not come with the N1c invaders to Europe and was already present there just like the bee keeping profession itself. In Sanskrit a word for wax is similar to those Volga-Permic languages "सिक्थ (siktha)".

- bee: mesilane, mehiläinen

- Sanskrit: मधुमक्षिका (madhumakSikA, madhu-maksika) (literally "mead-fly", "honey-fly")

- Albanian: menjë ("delicious drink, nectar")

The "S" from Estonian is changed to "H" in Finnish. The "-läinen" in Finnish means a resident of a place or a person belonging to some group or it is an adjective meaning relation to some place. Here it would mean that this "insect" belongs to honey (mesi, mehi).

- yellow: kelta

- Lithuanian: geltonas

- Samogitian: geltuona

- Old Saxon: gelo, gelu

- Latin: helvus ("honey-yellow")

- white: valkea, valko-, valga, vālda

- Lithuanian: baltas, balta

- Polish: białko ("the albumen of bird eggs")

- Polabian Drevani: algas ("tin")

- hoarfrost: härmä, härm

- Latvian: sarma

- Lithuanian: šarma

- Persian: سرما (sarmā)

- Old Armenian: սառն (saṙn)

- Ukrainian: сере́н (serén)

- Old Polish: śron

- Church Slavonic: срѣнъ (srěnŭ)

- death spirit: marras

More in the article about the Indo-European word for Death. This word surely goes back to the vocabulary of Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers that carried mainly the R1 haplogroup, which later split into R1a and R1b. The detected "Steppe Ancestry" in the Corded Ware Culture consists of mostly DNA from this genetic population with 18% of admixture from Early European Farmers and the rest being the Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer. If R1a-M558 and R1a-Z645 were already present in Estonia before the year 3000 BC then there was no need for R1b to bring this word into the area that already used it and this word certainly does not appear in the languages of Caucasus or EEF connected languages if that would be its source in the "Steppe Ancestry" Yamna Culture. The same pattern as in other Indo-European languages "death" words appear in the Estonian word "mere-" meaning sea.

- daughter: tütär', tytär, tidār, daktere, dakter, tütred ("daughters")

- Celtiberian: tuater

- Hittite: *duttariyatiyas ("of a daughter") (probably forged reconstruction based on Luwian)

- Norwegian Nynorsk: dotter

- Old Norse: dóttir

- Lithuanian: duktė̃

- identical, same: sama

- Sanskrit: सम (samá)

- Polish: sam, sama

- Old English: sama

- Gothic: 𐍃𐌰𐌼𐌰 (sama)

- Old Church Slavonic: самъ (samŭ)

- Old Irish: samail

- Albanian: -shëm

- Ancient Greek: ὁμός (homós) (for example in "homophony")

- Avestan: hama

- Persian: هم (ham)

- Northern Luri: هوم (hom)

If this word appears already in the R1a-Z93 Sanskrit, in Germanic R1a-Z284, in Slavic R1a-M458 and R1a-Z280 then why it would not appear in the R1a-M558 Indo-European Estonian and Finnish? There is no way to prove that it was loaned from exactly the Germanic branch...

- cloth, flax, string, linen, line: liina, lina

- Latin: līnum

- Gothic: 𐌻𐌴𐌹𐌽 (lein)

- Icelandic: lin

- Albanian: li

- Greek: λίνον (línon)

- Lithuanian: linas

- Russian: лён (ljon)

- Polish: len

- Latgalian: lyns

The long "ii" could come from "e" that would also be spelled as short "i", then maybe from "ei" or "ie".

- tar, pitch, resin of trees: pihka, pihku, pihk

- Latin: pix (piks)

- Dutch: pek

- Spanish: pegar

- Polish: pkieł

- Samogitian: pekla

- bitter: karvas, kōraz

- Hindi: कड़वा (kaṛvā)

- Urdu: کڑوا (kaṛvā)

- Old Church Slavonic: горькъ (gorĭkŭ)

- Belarusian: го́ркі (hórki)

This is one of few words that certainly goes back to the times of 3500 BC Indo-Aryan R1a-Z93 in Finnic but if it was loaned when the Indo-Aryans were near the Ural mountains then why in other Uralic languages it does not appear in the same form as in Hindi, Finnish and Livonian? In Komi-Permyak it is "курыт (kuryt)". Some people think that "karvas" is a loanword from the apparent Proto-Germanic "*harwaz" but it is a made up reconstructed word that has literally zero cognates in modern Germanic languages.

- greedy, voracious: ahnas (from *paznas or *zakhnas)

- Sanskrit: अश्न (azna, aśna)

- Polish: pazerna ("greedy woman"), zachłanny ("greedy man")

- trunk of a tree: kanto

- Sanskrit: स्कन्धस् (skandhas)

- spindle: värttinä (verttine)

- Old East Slavic: веретено (vereteno)

- Sanskrit: वर्तन (vártana) ("rotation, rolling, spindle")

- Latvian: vārpsta

- Slovak: vreteno

- Upper Sorbian: wrjećeno

- snake: käärme, kärm, kärv, keärmis, kīermõz, kiärmeh

- Persian: کرم (kerm) ("worm")

- Sanskrit: कृमि (kṛ́mi) ("worm")

- Polabian: carv ("worm")

- Slovak: červ ("worm")

- Lithuanian: kirmìs ("worm")

- Old Prussian: girmis ("worm")

- Old Irish: cruim ("worm")

- value, price: arvo

- Sanskrit: अर्घ (argha)

- Bactrian: argo

- Ossetian: arg

This would explain the other Indo-European meaning of Silver as "something of value", for example in Latin: "argentum" would be "something pricey" or "something to argue/haggle about".

- joint, together: jama (yama)

- Sanskrit: यमल (yamala) ("twin")

- might, power: mahti

- Gothic: 𐌼𐌰𐌷𐍄𐍃 (mahts)

- Dutch: macht

- Persian: magus

- Tocharian B: maiyyo

- Bulgarian: мощ (mošt)

This loan from Germanic exists only in the Finnish language. This is one of those few cases that it can be certainly said that it is a loanword.

- shame: häpeä, häbe, häpy (also could be from *siepa or *kepe)

- Polish: kiep

- Albanian: cipë (kip)

- Tocharian B: kip

- Tocharian A: kwīpe ("modesty, shame, pudency")

- English: wife (from *kwipe)

In Icelandic the etymology of the other word is explained as "kvensköp" meaning "women's shame".

- fart: peer, pieru, pierrä, peeretada, peerädäq, piirämä (from *peredek)

- Polish: pierd

- Mapudungun (Chile): perken

- Latvian: pirdiens

- Norwegian: fjert (from *pjert)

- Sanskrit: पर्दते (párdate)

- Belarusian: пярдзе́ць (pjardzjécʹ)

- Albanian: pordhë

- Ancient Greek: πορδή (pordḗ)

- field: pelto, peldo, pöud, põld, põlto

- Polish: pełto ("a field cleared from weeds")

- Polish: pole

- Sanskrit: प्रथान (prathāná) (from *plathana)

- Germanic: felt, feld

- Russian: поло́ть (polótʹ)

This was either borrowed from Germanic R1a-Z284 before the Grimm's Law occured or it is a normal substratum R1a-M558 word. If it was a borrowing that occured after the 500 BC then the Grimm's Law would surely occur and it would instead be loaned as "felto" in Finnish. Here Polish language (R1a-M458) amazes by the straight connection of their word "pełto", maybe this word already appeared in the European Neolithic and then was forwared with spread of the Corded Ware Culture steppe farmers. In Polish there are verbs such as "pielić" and "pleć", both meaning "to remove weeds".

- sage, wise, knowing: viisas, viekas

- Danish: vis

- Old Church Slavonic: вѣщь (věštĭ)

- Russian: ве́щий (véščij)

- Serbo-Croatian: ве́штац, véštac

- Polish: wiedzący (maybe similar to *viidsan)

- Sanskrit: विदु (vidu) ("wise")

- Lithuanian: vaidila

- thousand: tuhat, tuhad, tuha

- Old Swedish: þūsand

- Lithuanian: tūkstantis

- Latvian: tūkstotis

- Upper Sorbian: tysac

Again a proof that "H" in Finnic could come from "SK", "KS" or "S", more about that is described in the word article for Indo-European THOUSAND. The Indo-Aryan branch had no influence here at all, meaning that this word did not come from the R1a-Z93 Fatyanovo-Balanovo people.

- sister: sõsar, sõzār, sozor

- Latin: soror

- Kashubian: sostra

- Danish: søster

- Upper Sorbian: sotra

- Polish: siostra

Another Satem R1a-Z283 connection (parental to R1a-Z282 and R1a-M558)

- remember: meenuma, mäles

- Old Church Slavonic: мꙑсль (myslĭ)

- Latin: mens ("mind")

- Sanskrit: मानयति (mānayati) ("to think")

- Tocharian A: mäskatär ("to stay")

- Tocharian B: mäsketär ("to stay")

- Faliscan: 𐌌𐌄𐌍𐌄𐌓𐌖𐌀 (menerua)

- Mycenaean Greek: 𐀁𐀄𐀕𐀚 (e-u-me-ne, eumene)

- Ancient Greek: εὐμενής (eumenḗs), μένος (ménos)

- lake: jõra, järvi, järv, jaura

- Lithuanian: jūra ("sea")

- Armenian: ջուր (ǰur) ("water")

- wheel: ratas, ratti

- Sanskrit: रथ (ratha)

- Lithuanian: ratas

- Latvian: rath

- Old Saxon: rath

- Elfdalian: ratt

A word common with Germanic R1a-Z284 that does not appear in Estonia and Latvia but there is a connection to R1a-Z93 Indo-Aryan word for a chariot and R1a-Z282 and R1a-Z92 Baltic "ratas" so it could already be present with the Corded Ware Culture or even earliest cultures related to the Early European Farmers that used the wheeled wagons, but the Steppe people used them as well (Corded Ware Culture).

- thief: vargaz, vargas, varras, varas

- Kashubian: warg ("enemy")

- Sanskrit: वनर्गु (vanargu) ("thief, robber, a savage, wandering in a forest or wilderness")

- Russian: вор (vor)

- Lithuanian: voras ("spider")

- Chuvash: вăрă (vără)

- Lithuanian: vagis

- Lithuanian: vargas ("hardship, misery")

- Latvian: vārgs ("misery")

- Old East Norse: vargʀ ("wolf")

- Old Norse: vargr ("wolf, evildoer, destroyer")

- Old Persian: 𐎺𐎼𐎣 (varka) ("wolf")

- Old Saxon: warag ("criminal, reprobate, felon, monster, evil spirit")

- Bulgarian: враг (vrag) ("enemy")

- Polish: wróg ("enemy")

- Polish: warchoł (varkhol, varhol) ("criminal, reprobate, felon, monster, evil spirit")

- Komi-Permyak: вöрöг (vörög)

- Romanian: vrăjmaș ("enemy")

Again Kashubian forms a straight connection here, there is no connection to Tocharian languages.

- seed: siemen, šiemen, šiemeń, sīemgõz, seeme

- Slovak: semeno

- Old Church Slavonic: сѣмѧ ⱄⱑⰿⱔ (sěmę)

- Old Prussian: semen

- Oscan: 𐌔𐌄𐌄𐌌𐌖𐌍𐌄𐌝 (seemuneí)

- Paelignian: semunu

- eel (water snake): angerjas, ankerias

- Latin: anguis

- Old Prussian: angis

- Lithuanian: angis

- Latin: anguilla (could come from "anguis" + "illa", same as Hunter-Gatherer Germanic "eel")

- Sanskrit: अग (aga), अहि (ahi)

- Lithuanian: ungurys

- piglet, pork meat: porsas

- East Slavic: поросꙗ (porosja)

- Ukrainian: порося́ (porosjá)

- Lithuanian: paršas

- Polish: parszuk, prosię

- Old Prussian: prastian

- Umbrian: 𐌐𐌏𐌓𐌂𐌀 (porca)

- Latin: porcus

- Lusitanian: porcom

- Old Irish: orc

- Gaulish: orkos

- Old High German: farah (from *parak)

- Old English: fearh

- Avestan: pərəsa

The Germanic languages here are the evidence that this word was not a loan from those languages but instead arrived there in the times of the Corded Ware Culture or even earlier but it is closer to Balto-Slavic than to the Indo-Iranian branch.

- hawk: haugas, haukka, habuk

- Old English: hafuc (from *habuk or *kabuk)

- Old Norse: haukr

- Old High German: habuch

- Polish: kobuz, kobus

- Russian: ко́бчик (kóbčik)

- Latin: capus

- yoke: ike, ies

- Old Church Slavonic: иго ⰹⰳⱁ (igo)

- Slovene: igev

- Old English: ioc, ġioc, ġeoc

- cauldron: katel, kattila

- Latvian: katls

- Gothic: 𐌺𐌰𐍄𐌹𐌻𐍃 (katils)

- Latin: catīllus

- Sanskrit: कटोर (katora)

- Armenian: կաթսա (katʿsa)

- Belarusian: кацёл (kacjól)

- grain: jüvä, iva, jyvä, jiṿe

- Sanskrit: यव (yava) ("barley")

- Gujarati: જવ (jav) ("barley")

- Avestan: yauua ("cereal, grain, barley")

- Lithuanian: jãvas ("grain")

- Polish: jewnia, jownia ("granary for grain")

- Old Armenian: ջով (ǰov) ("sprout")

- Hittite: UDÚLe-wa-an (ewan) ("kind of grain; soup made of a kind of grain")

- Tocharian B: yap ("dressed barley")

- Kalasha: žo ("barley")

- Belarusian: ячме́нь (jačmjénʹ) ("barley")

- wooden shed, house, hut: kota, kata

- Danish: hytte

- Polish: chata (khata, hata)

- Ukrainian: ха́та (háta)

- Ancient Greek: καλύβη (kalúbē)

- Polish: chałupa (khalupa)

- Old Church Slavonic: кѫтъ (kǫtŭ) ("corner" as in "my own corner")

- leaf: lehti, leht, lasta, losst (from *lest')

- Russian: лист (list)

- Belarusian: ліст (list) ("a paper letter")

- Lithuanian: laĩškas ("a paper letter")

- Latvian: laiska ("leaf of a flax stalk")

It appears in all Finnic and Saami languages, while Corded Ware Culture did not reach the North of Finland but the Hunter-Gatherers of I1 did, so it is most probably a word of that origin, the Yamna Steppe people would have no purpose to bring their name for a "leaf" into Europe.

- fight: võitlus

- Old Church Slavonic: вои (voi) ("soldier, fighter")

- Polish: wojować

- Polish: wojsko ("army")

- Slovak: vojna ("war")

- Ingrian: voittaa ("to win")

- Veps: voida ("can, be able")

This word appears mainly in the Finnic branch of the Finno-Ugric languages and in the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages.

- bone: koht, kont

- Czech: kost

- Russian: кость (kost')

- forge: ahjo

- Swedish: ässja

- Gothic: 𐌰𐌿𐌷𐌽𐍃 (auhns) ("furnance")

- tribe, family: heimo, hõim

- Lithuanian: šeima

- Old East Slavic: сѣмиꙗ (sěmija)

- Russian: семья (semia)

- Latvian: sàime

- English: home

- piece: kappale, kabal

- Latvian: gabals

- Lithuanian: gabalas

- Polish: kawał

- Albanian: copë (kop)

- shepherd: paimoi, paimen

- Ancient Greek: ποιμήν (poimḗn)

- Lithuanian: piemuo

This could be related to Polish "poi męż" meaning "The man who gives water to someone" or Russian "пойма́ть (pojmátʹ)" meaning "to seize".

- wall: seinä, sein

- Latvian: siena

- Lithuanian: siena

- Bulgarian: стена́ (stená)

- Slovene: stena

- Latgalian: sīna

- Yakut: истиэнэ (istiene)

- haystack: suova (maybe from *stuoga)

- Belarusian: стог (stoh)

- Norwegian: høystakk

- Old Church Slavonic: стогъ (stogŭ)

- Lithuanian: stovas ("rack, stand")

- horn: sarv, sarvi, šarvi, saru, sarvvis, Sarvik, sǭra

- Sanskrit शरभ (śarabhá) ("horned animal; half-lion half-bird that slays lions; an eight-legged deer")

- Polish: sarna ("female horned animal"), sarniec, sarniak ("male roe deer")

- Belarusian: са́рна (sárna) ("chamois, mountain goat")

- Luwian: zarwanya, saruanya ("horn's")

- Hungarian: szarvas (sarvas) ("male deer")

- Lithuanian: karvė ("cow")

- Kashubian: karwa ("cow")

- Basque: sarrio ("chamois")

- Tocharian B: karse ("male deer")

- Old Church Slavonic: сръна (srŭna) ("roedeer")

- Avestan: sruuā, srū ("horn, claw, talon")

- Sanskrit: शृङ्ग (śṛṅgá) ("the horn of an animal")

- Czech: srnec ("male roe deer")

- Slovene: srna, srnjak

- Old Armenian: սրուակ (sruak)

- Old Prussian: sirwis ("horn")

- Persian: سرو (soru)

- Galician: cervo ("male deer")

- Latin: cervus ("deer, stag")

- Russian: се́рна (sérna) ("chamois")

Sarvik would then mean "The Horned One" and it is a proper name for The Devil but also a Underworld deity connected to Veles and cattle. This word does not appear in Western European Indo-European languages that mostly have the forms of "korn, karn, horn" coming from the Early European Farmer language. The Anatolian language Luwian presents the Satem form here, which is also very interesting. In Finnish a word for reindeer is "hirvas", which follows the typical pattern of "S" becoming "H" in this language or keeping the older "H" sound. In Slavic languages there is still the ancient masculine ending -ak, which would render Sarvik as a purely Indo-European word from *saru + *-ik.

- rye: rukis, ruis, ruiš, rüis, rugiž

- Lithuanian: rugys

- Old Norse: rugr

- Norwegian: rug

- Old East Slavic: ръжь (rŭžĭ)

- Polish: reż, ryż

- Upper Sorbian: rož

- Latvian: rudzi

- poppy: magun

- Latvian: magone

- *Chuvash: мӑкӑнь (măk̬ănʹ)

- Polish: mak

- German: Mohn

- Ancient Greek: μήκων (mḗkōn)

- Lithuanian: aguonà

- tetrix: teeri, teiri, teyri, töyri, teder, tedri, tetri, tetr (from *tetri)

- Latin: tetrix

- Czech: tetřívek

- Lithuanian: tetervas, titaras

- Polish: cietrzew

This bird appears only in Eastern Europe, Scandinavia and Italy

- soul: sielu

- Lithuanian: siela

- Norwegian: sjel

- Swedish: själ

- German: Seele

- Polish: siła ("the force")

- Gothic: 𐍃𐌰𐌹𐍅𐌰𐌻𐌰 (saiwala)

- Navajo: iiʼ sizíinii

- hook: aas, ansa, koukku

- Old Prussian: ansis

- Hindi: अंकुश (aṅkuś)

- Ancient Greek: ἀγκυλίς (ankulís)

- Latvian: āķis

- Polish: hak

- Urdu: ہک (huk)

- sister's husband: nuode

- Latvian: znots ("daughter's husband")

- Old Church Slavonic: зѧть (zętĭ) ("daughter's husband")

- Ancient Greek: γνωστός (gnōstós) ("blood relative")

- king: kunigaz, kuningas

- Lithuanian: kunigas

- Germanic: kuning, konungr, konge

- Old Church Slavonic: кънѧѕь (kŭnędzĭ)

- axe: tappara

- Old Armenian: տապար (tapar)

- Persian: تبر (tabar)

- Tajik: табар (tabar)

- Russian: топо́р (topór)

- Romanian: topor

According to Robert Sapolsky, the Finnish people do not differentiate between the sounds "B" and "P". This could be the same case in Persian and Tajik languages above.

- bucket, ladle: kauha, kosar, kassara

- Lithuanian: kaušas ("ladle, dipper, big spoon")

- Polish: kosz (koš)

- Bulgarian: ко́фа (kófa)

- Albanian: kovë (kov)

- Greek: κουβάς (kouvás)

- Polish: chochla ("ladle")

- Icelandic: ausa ("ladle")

- Ancient Greek: κύαθος (kúathos) ("ladle")

- Russian: ковш (kovš) ("ladle")

Estonian Bronze Age

The beginning of the Bronze Age in Estonia is dated to approximately 1800 BC. The first fortified settlements began to be built: Asva and Ridala on the island of Saaremaa and Iru in Northern Estonia. The development of ship building facilitated the spread of bronze. Changes took place in burial customs, a new type of burial spread to Estonian areas. Stone cist graves and cremation burials became increasingly common, alongside a small number of boat-shaped stone graves. Bright eyes, blond hair, fair skin and lactose tolerance became common only during the Bronze Age in Estonia and Finland and it was due to the influx of genes from the Corded Ware Culture invasion.

Around 700 BC a large meteorite hit Saaremaa island and created the Kaali craters. In the Finnish national epic Kalevala the cantos 47, 48 and 49 can be interpreted as descriptions of the meteorite impact, which resulted in a tsunami and devastating forest fires.

The Estonian Bronze Age genetic samples (EST_BA) come from the stone tombs that are believed to have been introduced into the Eastern Baltic from the Nordic Bronze Age civilization. In PCAs they overlap heavily with the Latvian Bronze Age samples (LVA_BA) and sit far away from the geographically closest Scandinavians. It means that most probably the culture of stone tomb burial did not come to Estonia with the physical arrival of the Nordic Bronze Age Scandinavians but instead it was an idea created by the local people. The Bronze Age Scandinavians would also bring the R1a-Z284 haplogroup in great amounts into Estonia and Finland but there was none of it detected and nowadays the amount of that haplogroup is very low (1% of all R1a) in modern Estonians.

A DNA sample from 750 AD of a man marked as VK487 from Saaremaa island was reported as R1a-CTS1211/R1a-M558 (subclade R-YP4932, connected to R1a-Z284). There is also a similar sample marked V9_2 from Joelähtme near Tallinn from around 1115 BC and X14_1 from Rebala also near Tallinn from around 605 BC. Those might be the ancestors of modern day Estonians who carry the R1a-Z284 haplogroup but it still appears scarcely in only 1% of all R1a haplogroups in Estonia, which would suggest that indeed there were some people coming from the Nordic Bronze Age area in Sweden to the coastal regions of Estonia, most probably as traders and merchants but still there wasn't a large influx of Nordic Bronze Age related DNA into the territory of Estonia, that would in turn make a big cultural impact on the Estonian Bronze Age population.

According to Saag 2019 study there was a growth of Hunter-Gatherer ancestors in the Bronze Age East Baltic genomes as compared to the previous European First Farmer (EEF) genomes. The genetic contribution from Siberia to the Eastern Baltic appeared only during the transition to the Iron Age around 500 BC. The arrival of Siberian ancestors coincides with the proposed arrival of the Uralic languages.

There was no other migration to Estonia between the Corded Ware Culture and the Iron Age migration of Siberian people who carried the Y-DNA N haplogroups. This migration of Uralic (Siberian) people caused a linguistic change in Estonia. A similar situation to that in Estonia, probably took place in Latvia and Lithuania! The Bronze Age native population of Estonia (R1a) was overlapped by foreigners (N) causing a change of language. In medieval Hungary, the invasions of linguistically foreign Uralic people (N1c) also caused a linguistic change. This could create an interesting conclusion that Slavic languages did not emerge from the break-up of the Balto-Slavic group, it was a foreign language change (Uralic) that came to the indigenous Northern Proto-Slavic language and in result created the Baltic branch.

This would mean that nowadays the Baltic languages are the ones closest to the Proto-Slavic language. When compared to Slavic languages they seem to be slightly changed by the Uralic influence. In this scenario both Baltic and Slavic languages would appear in the places that they are present nowadays (except for the Balkans, where they arrived after 500 AD) already with the spread of the Corded Ware Culture, not in 500 BC or even 500 AD.

In conclusion in the territory of Estonia, before the Iron Age, the Proto-Balto-Slavic language was spoken and that was the language closest to the Indo-Aryan languages. The Uralic people probably carried some loanwords from the Indo-Aryan languages but in the light of the theory and the list of vocabulary presented above, it is impossible to prove that those are indeed loans and not substratum words already present in Estonia and Finland (from the language of R1a-558, R1a-Z92 and R1a-Z280 people) before the Iron Age.

The Uralic Overthrow

This period saw a single Siberian Y-DNA haplogroup making up half of male lineages in Estonia (from 500 BC). The Iron Age split of Baltic Finnic not only coincides with the arrival of Nganasan-like ancestry in the region, but also with the climatic changes (cooling) between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, when reindeer herding pastoralism became necessary for survival. This is almost certainly why Corded Ware Culture (CWC) descendants adopted the culture, language and lifestyle of the incoming Uralic speakers, and mixed with them genetically to varying degrees depending on the group.

Interestingly modern Estonians show a bigger proportion of the Eastern Hunter-Gatherer component than the Corded Ware Culture individuals, this can only be explained by the later additional influx of DNA coming from the East. There are some certain Uralic words that do not appear in other Indo-European languages except for the Baltic branch:

- mushroom: siin', siini, sieni

- Manchu (China, East Asia): ᠰᡝᠨᠴᡝ (sence)

- Latvian: sēne

- Latgalian: sieņs

This word carried by the people with N1c haplogroup did not reach Lithuania and Old Prussia. The % of that haplogroup in the mentioned countries is also much lower than in Finland and Latvia (Estonia being the exception with 35%).

- house: maja

- Latvian: mājā

- brush: suka

- Latvian: suka

- yet: veel

- Latvian: vēl

- broom: luuta, luud, lud

- Latvian: slota

- Lithuanian: šlúota

- axe: kirves, kīraz, kirvõs

- Lithuanian: kirvis

- Latvian: cirvis

It maybe comes from the typical Indo-European word for an axe: *sekiraz, in Russian it is "секи́ра (sekira)", "σάγαρις (ságaris)" in Scythian, and "secūris" in Latin. This word does not appear in other Uralic languages.

- juniper: kadak, kadakas, kataja, kadag

- Latvian: kadiķis

- Lithuanian: kadagys

- Old Prussian: kadegis

A name given to Lithuania in Estonian is "Leedu" and to Latvia "Läti", those names could mean "People" in Indo-European. More information about those cognates are in the word article leode. In Estonian language Russia is called "Venemaa", "Veńa" in Veps language and in Finnish "Venaja", "Venädä". This would suggest that the Slavs were once called "Wens", "Veneti" or "Wends".

In the Late Iron Age, Estonians still burned their dead and buried them in stone graves, which had become more uniform than before. The number of burials and corpses also increased, and the first cemeteries were created. There was still a lot of jewelry brought to the dead, but not so many weapons and tools.

Parallels with Balto-Slavs

In the first verses of "Kalevipoeg" it is said: "In ancient days, the race of Taara dwelt here and there in the land, and took to themselves wives of the daughters of men. In the far North, near the sacred oak forest of Taara, such a household existed, and from thence three sons went forth into the world to seek their fortunes. One son travelled to Russia, where he became a great merchant; another journeyed to Lapland, and became a warrior; while the third, the famous Kalev, the father of heroes was borne to Estonia on the back of an eagle. The eagle flew with him to the South across the Gulf of Finland, and then Eastward across Lääne and Viru, until, by the wise ordering of Jumala, the eagle finally descended with him on the rocky shores of Viru, where he founded a kingdom"[7].

It is a very similar concept to that of "Lech, Czech and Rus" found for the first time in the "Polish–Hungarian Chronicle" from 1222 AD. The three brothers founded each Slavic state, Lech founded Poland (in Lithuanian: Lenkija, from Lęchia), Czech founded Czechia and Rus founded Kievan Rus (Belarus, Ukraine, Russia). Kalev is also the source for the name of Finnish "Kalevala", which means "The Land of Kalev".

Kalev dies, but before his death he prophesies the greatness of his unborn son: Sohni (Kalevipoeg, Kalevide, Son of Kalev). It is interesting that this youngest son is called in a typical Indo-European manner. Linda weeps for seven days and nights over her husband's death. Her tears create Ülemiste järv (situated in Tallinn). She then prepares him for his funeral and buries him 35 metres below the ground, constructing, as his burial mound, what is now known as the hill of "Toompea". This is yet another evidence that this story could occur only after the Kurgan invasion of the Corded Ware Culture into the territory of Estonia. During the Iron Age Estonians mostly creamted their dead until the Christianization of their territory, so the latest date for the arrival of Kalev to the territory of Estonia would be around 500 BC (Uralic) or earliest as an Indo-European kuningas 2700 BC (Corded Ware Culture) or 1800 BC (Bronze Age).

In Vepsian folklore there is a belief in the metamorphosis of the deceased person into a bird, mainly the cuckoo: "gathered and passed away before the warm fair summer, turned into light-winged bird, sweet cuckoo" (Zajceva and Žukova 2012: 138). In lamentations the cuckoo is the bird that liaises between the worlds of the living and the dead. Many lines in lamentations are devoted to this. The cuckoo is called on in trying moments. Vepsians address their requests to "bring news about late relatives" to the bird. This might be connected to the bird beliefs of people connected to the Lusatian Culture from the territory of what is nowadays Poland, Moravia and Slovakia.

According to the "Henric Chronicle Livoniae" ("Chronicle of Henry of Livonia") from 1222 AD the Estonians disinterred the enemy's dead and burned them. It is thought that cremation was believed to speed up the dead person's journey to the afterlife and by cremation the dead would not become earthbound spirits which were thought to be dangerous to the living.

The same chronicle from 1222 AD tells the story of "Tharapita, the great god of the islanders", who flew from Hiiemäe in Virumaa (mainland Estonia) to Saaremaa island (West Estonia). A similar figure is also mentioned in the "Knytlingasaga" written in Iceland in the 13th century. Namely, there were three idols of the pagan gods on the island of Rügen (then Slavic, nowadays German), whose statues were destroyed by the Danes around 1169 AD: Rinvi (Rugevit), Puruvit (Porevit) and Turupið (Porenut).

In addition, Bishop Feirgil or Aethicus Ister, who lived in Ireland in the 8th century, mentions in his book "Cosmogography" an island called Taraconta, which Lennart Meri and Urmas Sutropi thought could have been Saaremaa (Taarakund, Taarakond). In 1578 AD the Balthasar Russow described the solstice festival of Midsummer (Jaanipäev in Estonian) celebrating the Sun through solar symbols of bonfires (tradition alive until the present day) and numerous Estonian nature spirits of sacred oak and linden.

Together with ajatar (huntress) and akka (old woman), Syöjätär (literally "Eating Giant") fills similar roles in Finnish folklore as does Baba Yaga in Russian lore. There are also some similarities between Syöjätär and Russian folklore depiction of the devil – such as both being the origin of creatures like snakes and toads. Syöjätär lacks the positive side of the ambiguous Baba Yaga – this role is fulfilled by akka in Finnish myth.

The Estonian literary mythology describes the following pantheon: The supreme god is Taara. He is celebrated in sacred oak forests around Tartu, his other name is Uku. Uku's daughters are Linda and Jutta, the queen of the birds. Uku has two sons: Kou (Thunder) and Pikker (Lightning), who protect the people against Vanatuhi, the lord of the Underworld and demons. Pikker possesses a powerful musical instrument, which makes demons tremble and flee. He has a naughty daughter Ilmatutar (Air Daughter).

The Story of Kalevipoeg

The Kalevide (Kalevipoeg) meets a man of human stature who regales him with a story of giants. The Kalevide is amused and offers his protection. As was portrayed in the Nordic Bronze Age article the topic of giants originated in the belief system of the European Hunter-Gatherers and to some extent the Early European Farmers from Anatolia (Basques and Sardinians) but that EEF never reached the territory of Estonia physically (or rather biologically through a direct contact).

We can imagine that this story portrays the first contact of people from the Corded Ware Culture coming from the South with Northern European Hunter-Gatherers (Comb Ceramic Culture) living in the territory of Estonia and Finland around 3000 BC.

The Kalevide (Son of Kalev, Kalevipoeg) ponders a voyage to the end of the world. A great ship called Lennuk is created. The Kalevide meets a Laplander called Varrak who tells him that the end of the world is not reachable. He offers to take them home. The Kalevide says he needs no help to return home but would be grateful if Varrak would take them to the world's end. This becomes the voyage to an island of fire, steam and smoke where Sulevide gets scorched. They are found by a giant child who carries them to her father. The father requests that they solve his riddles for their release (This is Aarne-Thompson story type similar to type number 328: "the boy steals the giant's treasures"). They are successful and the daughter takes them to their boat and blows them out to the sea. The group carries on in their journey towards North. They witness the Northern lights and eventually come to an island of dog men (cynocephaly). After some troubles, peace is made with the dog men and their leader tells Kalevide that he has wasted his time and that he will never reach the world's end. The Kalevide finally decides to go home.

The Kalevide and his friends prepare for war. The Kalevide buries his treasure and protects it with incantations to Taara. The heroes engage in a fierce battle which lasts for many days and in which Kalevide loses his horse and Sulevide is badly injured. The Sulevide eventually dies. Olev builds a large bridge over the river Võhandu and the army proceeds over to engage the remaining enemy. The battle rages hard for many days until the heroes are exhausted and decide to drink. The Alevide slips and falls into the lake and drowns.

The Kalevide is so grief-stricken that he abdicates and places his kingdom in the hands of Olev. The Kalevide leaves for a peaceful life on the banks of the river Koiva. He does not get any peace that he desired and is often annoyed by many visitors. He wanders around the country annoyed by these intrusions and makes his way to Lake Peipus. He wades into Kääpa, the brook where he left his old sword, and the sword keeps its promise to cut off the feet of anyone who dares wade in the brook. Unfortunately the Kalevide had forgotten this promise and his feet are cut off. The Kalevide dies and is taken to heaven. However, he is deemed too valuable and is reanimated in his old body to stand guard for eternity at the gates of Põrgu to keep watch on Sarvik and his demons. He is there still tied to the gates of Põrgu by his hand, which is locked in a rock.

Estonian Kannel

This instrument is common with Latvian: kokle and kūkle, Finnish: kantelle, Lithuanian: kankles and Russian: gusli (гусли).

The first alleged evidence of the existence of gusli dates back to 591 AD. Its author, the Greek historian Theophylact Simokatta tells about three messengers of the Baltic Slavs who fled from the Avar Khan to Thrace and were taken prisoner by the Greeks. According to the historian, they had citharas (lyres) in their hands, however according to available information, the ancient Slavs could not have had any other musical instruments similar to citharas, except for gusli. The correctness of this assumption is confirmed by the later information of Arab writers about the instruments of the Slavs in the Southwestern part of present-day Russia.

The name "gusli" has been found in written sources since the 11th century. Etymologically it is associated with the words gusla, from the Old Russian meaning string. In Russian folklore (for example, in the epics about Sadko, Dobrynya Nikitich and Solov'e Budimirovich), such definitions are often used for voiced and springy harps, meaning an instrument with bright and loud sounding metal strings (containing gold and copper), in contrast to gusli with strings made of other materials like intestines, flax fiber or horsehair.

Modern Day Estonian DNA

Estonians and Finns show very little if any Mediterranean and African genes but on the other hand almost 10% of Finnish genes seem to be shared with East Asian and Siberian populations. Nevertheless, more than 80% of Finnish genes come from a single ancient Northeastern European population (genetically most similar to the ancient Corded Ware Culture).

Only 5% of all R1a1 Y-DNA in Estonia belongs to the purely Baltic R1a-Z92 subclade (common in Lithuania and Latvia), 20% belongs to the very ancient R1a-M558, 5% to R1a-M458 (purely West Slavic from Poland, Czechia and Slovakia), 1% to R1a-Z284 (from Norway and Sweden), the rest consists of deeply unclassified R1a-Z282 and R1a-Z280 clades. In general R1a makes up 30% of all Y-DNA haplogroups in Estonia.

R1b-M269 makes up around 9% of all Y-DNA haplogroups in Estonia. It is mainly represented by R1b-Y16878 found mostly in Sweden and Finland (from R1b-U152; Italic), R1b-Z198 (from R1b-P312; Celtic, Irish), R1b-U106 (Germanic) and R1b-Z326 (from R1b-U106). I1a (Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer related haplogroup) is around 20% in Estonia. In Finland the amount of R1a makes up around 5% of all Y-DNA haplogroups, R1b around 4% and I1a around 28%. N1c dominates in Eastern Finland and I1a in Western Finland. Finnish people share 47% of their autosomal DNA with the Western European Hunter-Gatherers (WHG). In Estonia there is also 5% of Y-DNA haplogroup I2a (Balkanic), 3% of E1b1b and 3% of haplogroup T.

N1c haplogroup ranges from 59% in Finland, 40% in Latvia and Lithuania, 35% in Estonia, 32% in Veps, 20% in Karelia, 14% in Podlaskie Voivodeship in Poland[8] and 10% in Belarus.

N1c is the characteristic genetic marker of the Nganasans and other Uralic people. Samoyedic people mainly have more N1b-P43 than N1c. Haplogroup N originated in the Northern part of China around 23000 BC and spread to Northern Eurasia, through Siberia to Northern Europe. Subclade N1c1 is frequently seen in non-Samoyedic people and N1c2 in Samoyedic people. The Baltic branch of N1c1 with DYS19=15 was established around 2000 years ago, it is typical of the inhabitants of Lithuania, Latvia and Old Prussia, while in Finland prevails the DYS19=14 of N1c1.

In the neighbouring Latvian population N1c, R1a, and I1 cover more than 85% of its paternal lineages. The Latvian Y-DNA gene pool was found to be very similar to those of Lithuanians and Estonians. Despite the comparable frequency distribution of N1c in Latvians and Lithuanians with the Finno-Ugric speaking populations from the Eastern coast of the Baltic Sea, the observed differences in allelic variances of N1c haplotypes between these two groups are in concordance with the previously stated hypothesis of different dispersal ways of this lineage in the region[9]. More than a third (33%) of Latvian paternal lineages belong specifically to a recently defined haplogroup R1a-M558, indicating an influence from a common source within Eastern Slavic populations on the formation of the present-day Latvian Y-chromosome gene pool[10].

Some Estonians and Finnish people carry the Delta 32 mutation in the CCR5 gene that appeared around 1000 BC after chickenpox epidemic in Central and Eastern Europe. That mutation is also common in Poland, Slovakia, Eastern Sweden and among Mordvins in Central Asia[11].

The populations of the Southern and Central regions of Estonia including Voru, Valga, Viljandi, Tartu, Saarema, showed the highest aDNA affinity towards Latvians and Lithuanians, additionaly those regions lacked the genetic affinity towards Finns and Swedes. Ida-Viru region in North-East of Estonia showed the highest affinity towards Finns[12].

Article created between the 17th of August and 10th of September 2021 (4 weeks of work). 7 new words added to Indo-European Estonian vocabulary on the 15th of Septemeber 2021 (for example horn, grey, yellow and kurgan).