Hallstatt Culture

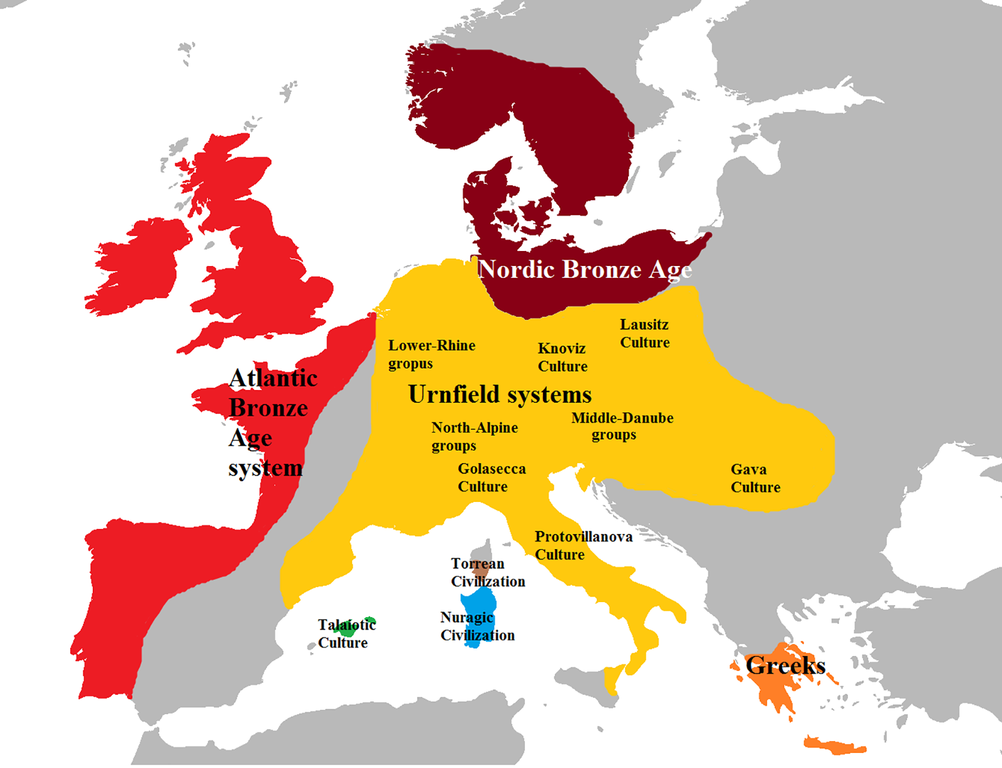

This culture existed from 1200 BC to 500 BC in the territory of Switzerland, Austria, Bavaria (Germany), Bohemia (Czech Republic), Northern Italy and Eastern France. It was preceded by the Unetice Culture and Urnfield Culture similar to the Lusatian Culture. The first Indo-Europeans settled in Switzerland around 2100 BC with the arrival of the Bell Beaker people from even earlier Corded Ware Culture. The Hallstatt Culture was followed by the Iron Age La Tène Culture.

It is named for its type site: Hallstatt - a lakeside village in the Austrian Salzkammergut Southeast of Salzburg, where there was a rich salt mine. Material from Hallstatt has been classified into 4 periods (Hallstatt: A, B, C and D).

The Lepontic Celtic language inscriptions of the area show that the language of the Golasecca Culture (1200 BC - 500 BC) was clearly Celtic, making it probable that the 13th century BC precursor language of at least the Western Hallstatt was also Celtic or Proto-Italo-Celtic. The Lepontic inscriptions have also been found in Umbria, in the area which saw the emergence of the Terni Culture, which had strong similarities with the Celtic cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène. The Umbrian necropolis of Terni, which dates back to the 10th century BC, was identical under every aspect, to the Celtic necropolis of the Golasecca Culture. A proof of a common origin of the P-Celtic, Umbrian, Oscan and Messapic languages and people will be revealead in DNA and vocabulary sections.

DNA

A male from 836 BC - 780 BC from Bylany, Bohemia, Czechia, who belonged to the Hallstatt Culture carried a Y-DNA haplogroup R1b-U152, another male from the same period carried a Y-DNA haplogroup R1b (depper subclades were not determined)[1].

A genetic study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America in June 2020 examined the remains of 5 individuals ascribed to either Hallstatt C or early La Tène Culture. The sample of Y-DNA extracted was determined to belong to haplogroup G2a-L497, while the 5 samples of mtDNA extracted were determined to belong to the haplogroups K1a2a, J1c2o, H7d, U5a1a1 and J1c-16261. The examined individuals of the Hallstatt Culture and La Tène Culture displayed genetic continuity with the earlier Bell Beaker Culture and carried about 50% Steppe related ancestry.

Nowadays R1b-U152 appears mostly in Northern Italy (over 50% of all Y-DNA), Corsica (over 50%), Switzerland (40%), France (35%), East England (20%, the Britonnic P-Celtic connection). The Y-DNA of the Habsburg family was also R1b-U152 (R1b-L2) and their origins go back to the the Habsurg village in Northern Switzerland.

In 2020 Furtwängler et al. analysed 96 ancient genomes from Switzerland, Southern Germany, and the Alsace region in France, covering the Middle and Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age. They confirmed that R1b arrived in those regions during the transitory Bell Beaker period from 2800 BC to 1800 BC. The vast majority of Bell Beaker R1b samples belonged to the R1b-U152 and R1b-L2 (from R1b-U152) clades (11 out of 14), the other being R1b-P312 (subclade of R1b-L11) and R1b-L51.

R1b-U152 would have entered Italy in successive waves from the Northern side of the Alps, starting in 1700 BC with the establishment of the Terramare Culture (1700 BC – 1150 BC) in the Po Valley. From 1200 BC a larger group of Hallstatt-derived tribes founded the Villanova Culture. This is probably the migration that brought the Italic-speaking tribes to Italy, who would have belonged mainly to the R1b-Z56 clade of R1b-U152. During the Iron Age, the expansion of the La Tène Culture from Switzerland is associated with the diffusion of the R1b-Z36 branch, which would generate the Belgae around modern Belgium and in the Rhineland, the Gauls in France, and the Cisalpine Celts in Italy[2].

Southern Italian populations show high similarity with those from the Middle East and Southern Balkans, while those from Northern Italy (Gauls, Italics, Umbrians) are genetically closer to populations of Northwestern Europe and Northern Balkans. Interestingly, the population of Volterra, an ancient town of Etruscan origin in Tuscany, displays a unique Y-DNA chromosomal genetic structure[2]. The North of Italy is dominated by R1b-U152 and R1b-S116 makes the second chunk of total R1b at around 15%. Corsican Y-DNA is differentiated by the high amount of R1b-M529 (the R1b-L21 abundant in the British Isles[3]), which appears only in Southern Italy and is absent in Northern Italy.

R1b-U106 (subclade of R1b-L11 found in Bell Beaker and Hallstatt samples) on the other hand is absent in Corsica and is quite common in whole Italy being the third R1b subclade. R1b-L23 (paternal to Yamnaya, Hittite and Albanian R1b-Z2103, but also to R1b-L11 and R1b-U106; most probably samples without deep subclades determined) appears in all regions and peaks at 25% in Sicily. R1b-M412 (direct subclade of R1b-L23 but brotherly to R1b-Z2103) makes up 60% of all R1b in Southern Apulia region (sole of the shoe) of Italy.

One common R1b subclade in Britain is R1b-U106, which reaches its highest frequencies in North Sea areas such as Southern and Eastern England, the Netherlands and Denmark but also Corsica. Due to its distribution, this subclade might be associated with the Anglo-Saxon migrations. Ancient DNA has shown that it was also present in Roman Britain, possibly among descendants of Germanic mercenaries.

Other samples with sizeable British-like ancestry include VK177 (32.6%, Y-DNA R1b-U152), VK173 (33.3%, Y-DNA I2a1b1a), or VK150 (25.6%, Y-DNA I2a1b1a), while typical Germanic subclades like I1 or R1b-U106 tend to show less.

Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Northwestern England are dominated by R1b-L21 (R1b-M529), which is also found in Northwestern France, the North coast of Spain, and Western Norway. This lineage is often associated with the historic Celts, as most of the regions where it is predominant have had a significant Celtic language presence into the modern period and associate with a Celtic cultural identity in the present day. It was also present among Celtic Britons in Eastern England prior to the Anglo-Saxon and Viking invasions, as well as Roman soldiers in York who were of native descent.

One interetsing fact is that the Y-DNA haplogroup of the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose IV, Amenhotep III and his grandson Tutankhamun was R1b1a1b (R1b-V1636 that formed around 4600 BC). A male of the Botai Culture in Central Asia buried around 3500 BC carried R1b1a1 (R1b-M478) but and earlier Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer buried near Samara, Russia 5000 BC carried the R1b1a1a haplogroup. This would mean that the ancestor of the pharaoh Thutmose IV was an Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer.

Gallery Of Artifacts

Vocabulary

Words below come mostly from Oscan, Umbrian, Latin, Welsh, Breton, Irish, Lusitanian and Gaulish languages. People carrying the R1b-L151 (R1b-L11) Y-DNA haplogroup were already in contact with people carrying the R1a-Z283 Y-DNA haplogroup in Bohemia, Czechia around 2900 BC. Words below could either be traced back to this time or even earlier times of paternal R1 haplogroup carried by all ancient Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers.

One of the oldest sentences from the Italo-Celtic branch comes from the Palestrina brooch in Italy: "Manios med fhe-fhaked numasioi", meaning "Manios me fashioned (created) for Numasios". The word "fhaked" is connected to English "fashion", in Latin and Faliscan it is "faciō", in Umbrian "𐌚𐌀𐌊𐌖𐌌 (fakum)" meaning "to do".

- four: 𐌐𐌄𐌕𐌖𐌓 (petur), 𐌐𐌄𐌕𐌕𐌉𐌖𐌓 (pettiur), petranioi, petguar, pedwar, peuar

- Lithuanian: keturi

- Old Prussian: keturjāi

- Thracian: ketri-

- Old Irish: cethair (ketair)

- Romanian: patru

- Latin: quattuor

- Latin: quartus ("fourth")

- Asturian: cuartu ("fourth")

- Polish: czwarty (čvarty, *čŭartū)

The "𐌐𐌄𐌕𐌖𐌓 (petur)" in Umbrian, "petranioi" in Lusitanian Celtic and "petuar" in Welsh indicate that the change of "K" or "KU" to "P" occured in the Italo-P-Celtic Hallstatt Culture. The Latin tribes most probably arrived in Italy earlier with spread of the Unetice Culture or Bell Beaker Culture that also gave rise to the Q-Celtic Gaelic languages.

- five: pomp, penka, pempe, pemp, 𐌐𐌖𐌌𐌐𐌄 (pumpe), pump, cóic, quīnque

- German: fünf (*punp)

- Norwegian: fem

- Lithuanian: penki

- Polish: pięć

The Messapic word "penka" seems to be closest to a Lithuanian word "penki". Nowadays the territory of Italy that was once inhabited by the Messapians is dominated by the Y-DNA subclade R1b-M412 that does not occur in Lithuania. The closest cognate to Oscan and Umbrian "𐌐𐌖𐌌𐌐𐌄 (pumpe)" is Welsh "pump" and German "fünf (*punp)" again indicating that P-Celtic Welsh and Gaulish like Umbrians and Oscans originate in a common Hallstatt Culture language but Latins with their "KU" in "quīnque" would come earlier with the Bell Beaker derived Terramare Culture. A word for "fifth" in Irish is "cúigiú (kuigiu)" and it is very similar to Latin "*kuingue", which supports this common Latin-Gaelic Bell Beaker origin theory. Other words for five are Old Irish "cóic", Manx "queig", Scottish Gaelic "còig".

- nine: 𐌍𐌖𐌅𐌉𐌌 (nuvim), novem, nove, nonam, nav, naw, naoi

- Sanskrit: नवन् (navan)

- Tocharian A: ñu

- *Zazaki: new

- German: Neun

- hundred: kant, cant, centum, cét, céad

- Tocharian A: känt

- Tocharian B: kante

- Sanskrit: शत (śatá)

- Polish: setka

- *Southern Mansi: šɛ̮̄t

Again Q-Celtic and Latin differs by "KEN", "KEA" when compared to P-Celtic "KAN" in this word. It seems that Irish and Latin is closer to Tocharian A in this matter and P-Celtic is closer to Tocharian B.

- who: kue, qui, quis, quem

- Norwegian: hvem

- Finnish: ken

- Ossetian: чи (ḱi)

- Persian: کی (ki)

- Faroese: hvør

- Old English: hwā

- Gothic: 𐍈𐌰𐍃 (ƕas)

- Old Church Slavonic: къто (kŭto)

- and: 𐌀𐌍𐌕 (ant), uta, et, agus, a

- Sanskrit: अन्ति (anti) ("near")

- *Basque: eta

- ear: glust, cluais, cleaysh, auscultō (all meaning "the hearers")

- Ancient Greek: κλύω (klúō)

- Lithuanian: klausyti ("to listen"), klausau ("I listen")

- Tocharian B: klyaus- ("to hear")

- Welsh: clywed (kluuet) ("to hear")

- Sanskrit: श्रुति (śrúti) ("hearing, listening")

- Ossetian: хъусын (qusyn) ("hear")

- Old Church Slavonic: слꙑшати (slyšati) ("to hear")

- grandson: nepos, nipot

- Albanian: nip

- Old Lithuanian: nepuotis

- Sanskrit: नपात् (napāt)

- Hindi: नवासा (navāsā)

- Latgalian: unuks

- Lithuanian: anūkas

- Old East Slavic: вънукъ (vŭnukŭ)

- *Hebrew: נֶכֶד (nekhed)

- *Kyrgyz: небире (nebire)

This word does not appear in the languages of the R1a-Z284 tribes related to the Nordic Bronze Age and R1a-M558 language in Estonia and Finland. Most probably because the kinship system there was still dominated by the Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer groups and this Forest-Steppe Yamnaya (Eastern Hunter-Gatherer) word or Early European Farmer word (more probable) appeared strongly in the R1b and R1a-Z93 and R1a-M458 tribes instead. Slavic "-nuk" and Hebrew "nek-" would indicate the Early European Farmer (EEF) origin. This word does not appear in the P-Celtic and Q-Celtic languages, in Welsh it is "wyr", in Irish "garmhac".

- young (soft, weak): moldus, mollis, mol

- Old East Slavic: молодъ (molodŭ)

- Belarusian: малады́ (maladý)

- Old Prussian: maldai

- Old Church Slavonic: младъ (mladŭ)

- Kashubian: młodi

- Sanskrit: मृदु (mṛdú)

- English: mild

- Old Armenian: մեղկ (mełk)

- tooth: dant, dans, det, dēns, dentēs, 𐌃𐌖𐌍𐌕𐌄 (dunte)

- Sanskrit: दन्त (dánta)

- Old Prussian: dantis

- Lithuanian: dantìs

- Middle Low German: tant

- Ossetian: дӕндаг (dændag)

- Gothic: 𐍄𐌿𐌽𐌸𐌿𐍃 (tunþus)

- Russian: десна́ (desná) ("gums")

- Polabian: ďǫsnă ("gums")

- Irish: fiacla

poet, singer, speaker, invoker, praise-maker, reciter: bard, barth, barz, barn

poet, singer, speaker, invoker, praise-maker, reciter: bard, barth, barz, barn- Armenian: կարդամ (kardam) ("to shout, to call, to recite loudly", "to read")

- Czech: bředit ("to chatter")

- Albanian: bërbëlit ("to chatter")

- Sanskrit: गृणाति (gṛṇā́ti) ("to invoke, to recite, to relate")

- Latin: grātus ("grateful, thankful")

- Albanian: grah ("to recite, to roar")

- Old Prussian: girtwei ("to praise")

- Lithuanian: gìrti ("to praise")

- Lithuanian: kereti ("to cast spells")

- Polish: czarować ("to cast spells")

- Old Church Slavonic: жрьти (žrĭti), жрѣти (žrěti) ("to offer sacrifice")

- Polish: żerca ("the pagan Slavic priest", "the one who offers to the Gods")

- Czech: žert ("amusing story", "joke")

- Polish: żart ("amusing story", "joke")

In Ancient Greek there is a word "χᾰ́ρτης (khártēs)", which means "paper" (English "card"). This noun comes from a verb "χαράσσω (kharássō)" meaning "I scratch, I inscribe" and it is cognate to a Lithuanian verb "rašyti" meaning "to write". First there were words for "speaking, reciting and pleasing" and then this "speaking" would be written down, for example in Linear B. The ancient people considered the written symbols to be a "speech magically bound to paper" and paper itself was "the thing that speaks or tells a story". In Phoenician there is a word "ḥrṭit (𐤇𐤓𐤈𐤉𐤕, Hebrew letters חרטית, ḫartit)" interpreted as "something written".

In the Oscan language a word for "praise" is "𐌁𐌓𐌀𐌕𐌄𐌝𐌔 (brateís)" and in Paelignian it is "brat, brais" but in Latin it is "grātēs". This "B" in Oscan and Paelignian instead "K" in Latin The earliest name of a Celtic "Bard" would then most probably be "Gart" (related to English "gratification"), literally "The One Who Praises The Gods" or "The Gratifier".

This reconstructed form "*gart" is strictly connected to a Polish word "żart" because most of the words beginning with "ż" or "zh" in the Polish language come from and earlier "g" or "kh". Nowadays this word means a "joke" and in my opinion it changed its meaning from an original meaning of "prayer" into a "joke" because of the Christian priests, who very often switched the meaning of pagan Slavic vocabulary into something "stupid". The dictionary of English language keeps that older meaning of a "joke" as "an amusing story". There is another proof for the same diminishment of the original Indo-European meanings, which occured in the Old Cornish word "barth", which later in history became just another name for a "jester".

In other Indo-European societies a function of a bard was fulfilled by skalds, rhapsodes, minstrels and scops. A hereditary caste of professional poets in the Indo-European society has been reconstructed by comparison of the position of poets in medieval Ireland and ancient India in particular. One of the most notable bards in Irish mythology was Amergin Glúingel, who was also a druid and a judge of the Milesians.

- true, reliable, faithful: berus, vērus, feer, fír, fìor, guir

- Polish: wierny

- Old English: wǣr

- German: wahr

- Old Church Slavonic: вѣра (věra) ("faith")

- horn: karn, cervus, cervo

- Doric Greek: κᾰ́ρᾱνον (kárānon)

- Polish: sarna ("female horned animal"), sarniec, sarniak ("male roe deer")

- Belarusian: са́рна (sárna) ("chamois, mountain goat")

- Luwian: zarwanya, saruanya ("horn's")

- Sanskrit: शृङ्ग (śṛṅgá) ("the horn of an animal")

- king, ruler: rēx, rix, ri, rige, righ

- Old Norse: rekr

- Sanskrit: राजन् (rā́jan)

- Gothic: 𐍂𐌴𐌹𐌺𐌹 (reiki) ("kingdom")

- ship: nausum, nāvis, nave, nau

- Sanskrit: नौ (naú), नावा (nāvā́) ("ship"), नाव्य (nāvyá) ("boatable, navigable")

- Persian: ناو (nâv)

- Ancient Greek: ναῦς (naûs)

- Old Armenian: նաւ (naw)

- Old English: nōwend

- Old Norse: nǫkkvi

- small: petitus, petit, pequeno, piccolo, piccino

- Ancient Greek: τυτθός (tutthós)

- Polish: tyci

- Sanskrit: तनु (tanu)

- English: tiny

- Tocharian B: totka

- Armenian: պատառ (pataṙ) ("piece")

- *Udi: пӏатӏар (ṗaṭar)

- *Udmurt: пичи (pići)

- *Chuvash: пӗчӗк (pĕč̬ĕk)

- *Georgian: პატარა (ṗaṭara)

- *Finnish: pikkuinen

- male goat: bouch, boc, bwch, bukk

- Old Norse: bukkr

- Norwegian: bukk

- Sanskrit बुख (bukha)

- Avestan: būza

- Persian: بز (boz)

- Old Armenian: բուծ (buc) ("lamb")

- Polish: buc ("stubborn person")

- warrior: cing, cingetos, kingetos

- Polish: zwycięzca ("winner")

This word is connected to German "Krieg" through the meaning of "burden of war", "something heavy". Word for heavy in Polish is "ciężar" and would come from earlier "*ciengar" or maybe "*kingar" by following this reconstruction we can recreate the meaning of English "king" as "man under burden" related to "burden of a crown". In Old Irish "cing" means "warrior, champion".

- tribe, kinship: toutā, toutad, totam, toticu, tut, teuta, tuatha

- Phrygian: τευτους (teutous)

- Old Prussian: tauto

- Latvian: tauta

- Gutnish: tjaud

- Old Norse: þjóð

- Old English: þēod

- Persian: توده (tōda)

- Albanian: tëtanë

- Gothic: 𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰 (þiuda)

- *Etruscan (500 BC): θuta (thuta)

- thunder (sound not lightning): tono, tonus, tonitrus, torann, taran, Taranis, tronada, tonnerre

- Persian: تندر (tondar)

- German: Donar ("The Thunderer")

- Polish: taran ("ram")

- Faroese: tora

- Norwegian: torden

- Old English: þunor, þur

- Tajik: тундар (tundar)

- Sardinian: tronu

- Polish: grom, dudni

- Swedish: dunder

- Croatian: tutanj

- Czech: dunění

- old: senex, sené, sen, sean, shenn, hen

- Sanskrit: सन (sána)

- Latvian: sens

- Lithuanian: senas

- Gothic: 𐍃𐌹𐌽𐌴𐌹𐌲𐍃 (sineigs)

This finally proves that the Bell Beaker Culture (from Corded Ware Culture) related to Q-Celtic and Latin best preserved the original name for "old". In P-Celtic "S" switched to "H" just like it did in Avestan "hana" or Ancient Greek "ἕνος (hénos)".

- dog: ᚉᚒᚅᚐ (cuna), cù, coo, ci, canis (kanis)

- Tocharian A: ku

- Old Norse: hundr

Here Irish is closer to Gaulish and Germanic instead of Latin.

- guest: hostis, hospes, hôte, kośio, güéspede

- Czech: host

- Latgalian: gosts

- Polish: gość

- Old Church Slavonic: гость (gostĭ)

- Proto-Norse: gastiz

- Gothic: 𐌲𐌰𐍃𐍄𐍃 (gasts)

- Belarusian: госць (hoscʹ)

- English: host

- Old Norse: gestr

- *Tigrinya (in Africa): ጋሻ (gaša)

Latvian and Lithuanian use different words for a guest: "viesis" and "svečias".

Bell Beaker Culture Irish vs. Hallstatt Culture Welsh:

- squirrel:

- Irish: iora

- Manx: fiorag

- Welsh: wiwer

The Welsh word is cognate to Polish "wiewiórka", Aromanian "viviritsã", Latvian "vāvere", Latin "viverra", Gilaki "وروره (varvarə)", Old English "ācweorna", while Manx "fiorag" is the most similar to Old English form "-wiorna" and Polish "-wiorka".

- pig:

- Irish: muc (muk)

- Welsh: mochyn (mohun)

- cave:

- Irish: uaimh

- Welsh: ogof

Three early Bronze Age men (2026 BC – 1534 BC) from burials on Rathlin Island off the Northern coast of Ireland were all R1b1a2a1a2c (R1b-L21, absent in Northern Italy), Rathlin2 was further defined as R1b1a2a1a2c1 (R1b-DF13/S521/CTS241), Rathlin1 was further defined as R1b1a2a1a2c1g (R1b-DF21/S192). Haplogroup R1b-L21 descends from the R1b-L151 (R1b-L11, with earliest samples found in the Corded Ware Culture males in Czechia, Bohemia around 2900 BC, related to the Bell Beaker Culture) that later also produced the R1b-U106 that is very common in Italy.

Tuatha de Danann

They might represent the final Indo-European tribes that invaded the British Isles and originated in the Hallstatt Culture. Their god of smiths was called "Govannon" in Wales, "Goibniu" in Ireland and "Gobanos" in Gaul, both names are related to Slavic verb "kovati" meaning "to strike" or "work in smithy" and Slavic name for a smith "koval".

Their main goddess was "Danu" (Dan, Dana, Dann, Don, Anu) and she is the same goddess as Hindu "Danu" (she was a mother of "Vritra"), in Latin the name for "Dunai" was "Danubius" and this river goes through the territory of Austria and Southern Germany (Hallstatt Culture in the past). Those names could be connected to Slavic "toń" meaning "depth" and verb "tonut'" and "tonąć" meaning "to drown".

The Dagda's name might be connected to a Cimmerian king Dugdamme (Tugdamme, Dugdam), whose name supposedly means "Good Giver". The Welsh word for "good" is "da" or maybe it is a very ancient word connected to Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer because in Ingush and Chechen languages it is "дика (dika)". The Cimmerians belonged to Y-DNA haplogroups: R1b1a, Q1a1 (ANE or Seima-Turbino), R1a-Z645 (R1a-M417), R1a2c-B111.

The Callanish Stones are cross-shaped setting of standing stones erected around 3000 BC and one of the most spectacular megalithic monuments in Scotland. The earliest Fomorians ("fo" + "mor" meaning "after plague") would then represent the Western European Hunter-Gatherer people who survived the bubonic plague. The first evidence for that disease appears in the Megalithic Funnelbeaker Culture around 2900 BC and even earlier in a Hunter-Gatherer population from Riņņukalns, Latvia around 3300 BC[4][5][6]. The names of Fomorians were for example: Balor (cognate is in Greek name "Βελλεροφόντης (Bellerophontes)" meaning "slayer of Belleros"), Conann, Bran mac Llyr, Febar, Buarainech, Cethlenn, Banba, Corb, Ériu.

A similar figure to Balor appears in the Basque myths: "Tartaro", "Tartalo". The story is similar to that of Odysseus and Polyphemus (Cyclops). Tartalo started to look for the boy, who blinded him, among his sheep, but he put on a sheep's skin and escaped. Tartalo got out of his cave and he started to run after the ring screaming ring worn by the boy. The young one wasn't able to take off the ring, so when he arrived to the edge of a cliff, he cut off his finger, and since Tartalo was near, he decided to throw it down the cliff. Tartalo, following the ring's shouting, fell off the cliff. Other evil one-eyed figure would be Cantabrian Ojancanu (Ohankanu) and female Ojancana. They were the embodiment of cruelty and brutality.

The second leader of second human invasion to Ireland (probably Bell Beaker Culture) was called Partholon and later his people died from bubonic plague. After him the Nemed came to Ireland from Scythia with his people on 44 ships. Later they were enslaved by the Fomorians and had to make offerings to them and perform human sacrifices. Then Morc waged war against them and only 30 Nemedians survived. Ireland became a wasteland for the next 200 years until they came back as Fir Bolg people ("Men of the Bags"). When Tuatha de Danann arrived, Cian with help of the female druid called Biorg saved the daughter of Balor - Ethlinn and then she had a son Lugh Lamhfada (the grandson of Balor), who killed his grandfather with a spear. The king of the Tuatha de Danann lost his right arm when fighting with Fir Bolg people and then he was killed by Balor in battle.

Finally the Gairthear Mílidh Easpáinne (Milesians) overthrowed the Tuatha de Danann and became the first human kings of Ireland, Fionn mac Cumhail was one of them but his grandgrandfather was Nuada from Tuatha de Danann.

Unetice Horses

A new study from 2021 on horse DNA in Western Europe suggest that the DOM2 type horse ancestral to modern European horses spread with the Unetice Culture warriors (2300 BC - 1600 BC) rather than Bell Beaker Culture warriors (2800 BC - 2300 BC)[7].

The globalization stage started when DOM2 horses dispersed outside their core region in Ukraine, first reaching Anatolia, the lower Danube, Bohemia (Unetice Culture) and Central Asia by approximately 2200 to 2000 BC, then Western Europe and Mongolia soon afterwards, ultimately replacing all local populations by around 1500 to 1000 BC[7]. This would mean that also the horse-related Indo-European vocabulary (like Italian "equus", Irish "ech (ekh)", Celtiberian "ekua" or P-Celtic "epos" and "eb") became more widespread only after 2000 BC in Western Europe.

The large variability and repeated diminution in size of horses in the Early Bronze Age (2200 BC - 1700 BC) could indicate advanced domestication or multiple origins of the populations (or both). The persistence of wild horses in the Early Bronze Age can not be proved osteometrically, but the presence of domesticated horses is considered certain[8].

Article created in September 2021 and published on the 8th of October 2021