Indo-European Armenia

Hayk was a handsome, friendly man, with curly hair, sparkling eyes and strong arms. He was a man of giant stature, a mighty archer and a fearless warrior. Hayk and his people had migrated South toward the warmer lands near Babylon. In that land there ruled a wicked giant named Bel. He tried to impose his tyranny upon Hayk's people. But proud Hayk refused to submit to Bel. As soon as his son Aramaniak was born, Hayk rose up and led his people northward into the land of Ararad. At the foot of the mountain he built a village and gave it his name, calling it Haykashen.

Hayk would then be an etiological founding figure like Asshur for the Assyrians. One of Hayk's most famous scions Aram settled in Eastern Armenia from the Mitanni Kingdom (Western Armenia). When Sargon II mentions a king of part of Armenia who bore the (Armenian-Indo-Iranian) name Bagatadi (which like the Greek-based "Theodore" and the Hebrew-based "Jonathan" means "God-given").

Some sources claim that Hayk is derived from the Urartian deity Ḫaldi. Armenian historiography of the Soviet era connected Hayk with Hayasa mentioned in Hittite inscriptions. The Armenian word Haykakan or Haigagan (Armenian: հայկական, meaning "that which pertains to Armenians") finds its stem in this progenitor. Additionally, the poetic names for Armenians, Haykazun (հայկազուն) or Haykazn (հայկազն) also derive from Hayk.

At Dyutsaznamart (Armenian: Դյուցազնամարտ, "Battle of Giants"), near Julamerk Southeast of Lake Van, on August 11, 2492 BC (according to the Armenian traditional chronology of the first month of the Armenian calendar, Navasard or 2107 BC (according to "The Chronological table" of Mikael Chamchian), Hayk slew Bel with a nearly impossible shot using a long bow, sending the king's forces into disarray. The hill where Bel with his warriors fell, Hayk named Gerezmank meaning "tombs". He embalmed the corpse of Bel and ordered it to be taken to Hark where it was to be buried in a high place in the view of the wives and sons of the king. Soon after, Hayk established the fortress of Haykaberd at the battle site and the town of Haykashen in the Armenian province of Vaspurakan (modern-day Turkey). He named the region of the battle Hayk, and the site of the battle Hayots Dzor.

Lchashen Metsamor

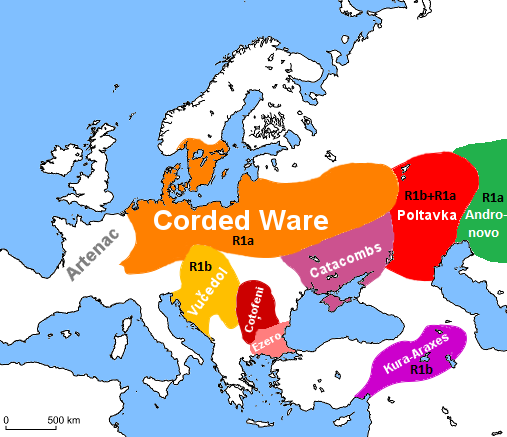

The Lchashen-Metsamor Culture (1500 BC - 700 BC) emerged from an earlier Trialeti-Vanadzor Culture (2400 BC - 1700 BC), the successor of local non Indo-European Kura-Araxes Culture (zero Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer or Yamna related genetic ancestry in the samples).

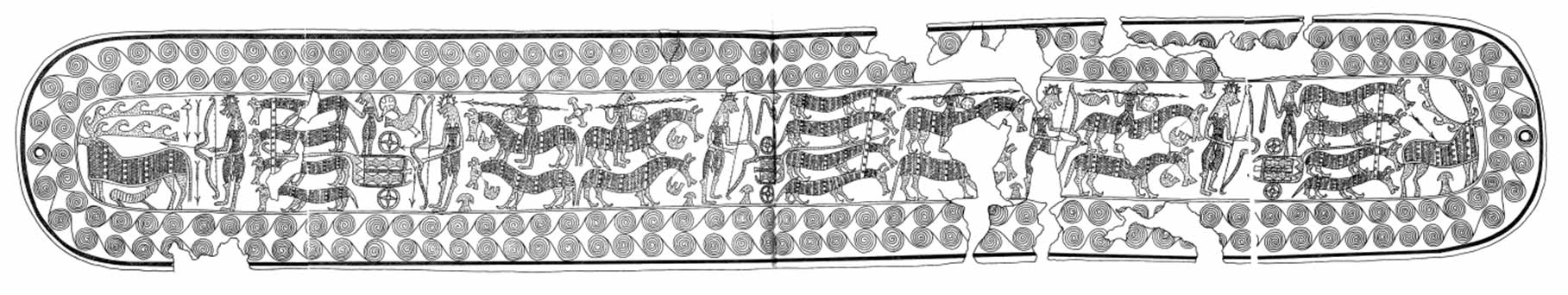

People associated with the Lchashen Metsamor archeological culture were among the earliest in Transcaucasia and the Near East to use the revolutionary spoke-wheeled horse chariot. A fully preserved four-wheeled chariot was found at Lchashen.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of West Eurasian genetic variation suggests that the Lchashen Metsamor pair (labeled Armenia_MBA_Lchashen), as well as most of the other currently available samples from what is now Armenia dating to the Middle to Late Bronze Age (MLBA), harbor Yamna related ancestry. That's because they appear to form a cline between samples associated with the Sintashta and Kura-Araxes cultures.

The Kura-Araxes Culture was a major Early Bronze Age (EBA) archeological phenomenon centered on Transcaucasia and surroundings, so its population can be reasonably assumed to have formed the genetic base of most subsequent populations in the region. The Sintashta Culture originated from the Corded Ware Culture derived Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture. The Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture and its R1a-Z93 has its origins in the region around Carpathian Mountains (Southern Poland, Western Ukraine, Moldova and Eastern Romania).

CWC_Kuyavia (Corded Ware Culture samples from present-day Kuyavia, North-Central Poland) and Balkans_BA_I2163 (a Bronze Age singleton from what is now Bulgaria) are both very similar and probably closely related to each other and to the Sintashta samples. Morphological data suggests that the Sintashta Culture might have emerged as a result of a mixture of Steppe ancestry from the Fatyanovo-Balanovo, Poltavka and Catacomb Culture, with ancestry from Neolithic Forest Hunter-Gatherers.

An article by Damgaard (2018) dedicated to the genetic study of ancient inhabitants of the Eurasian Steppes published the ancient DNA of two people from Lchashen burials. Samples included Y-DNA I2a2b-L596 (common in Southern and Eastern Europe) and mitochondrial DNA HV0a (common in whole Europe, especially Scandinavia) and J1b1a (Near Eastern).

The genetic data on horses shows that modern domesticated horses (DOM2 type from Western Ukraine) were introduced to Anatolia only after 2000 BC, this could coincide with the spread of the spoke-wheeled chariots to Armenia with the late Trialeti Culture or early Lchasen-Metsamor Culture[2]. Horses were already present in the Early Bronze Age Nerkin Naver settlement around 2300 BC[3]. The Akkadians and Hurrians used the word "sisium" and "issi" for a horse. This word was first attested around 2000 BC and is believed to come from the Indo-European source. Sometimes it was written as "KUR anshe". This might be related to the Satem "asua" root for a horse, Sanskrit "अश्व (aśva)", Belarusian "асёл (asjól)", Hurrian: "𒀸𒋗𒉿 (aš-šu-wa)".

It is possible that Indo-European speaking Armenians reached the territory of Eastern Anatolia as early as 2000 BC from the Trialeti Culture. The earlier date of 2400 BC should be further supported by the genetic evidence but this would mean that they imported new type of horses only after 2000 BC and later chariot warfare around 1600 BC instead of brining this into the region with their earliest migration[4][5]. Their presence as the successors to the local Urartians can be dated to approximately 520 BC, when the names Armina and Armaniya first appear in the Old Persian cuneiform inscription of Darius I.

Below is a Bronze Belt from Metsamor on which the spoke-wheeled chariots drawn by four horses are clearly visible:

💀 Crypts discovered during the excavations of Lchashen (the grave field has around 800 graves and tombs, most of which have a form of stone cases) represent an exceptional collection of the Bronze Age culture. The uniqueness of Lchashen’s graves is that some of them had skeletons of horses and oxen harnessed to wagons as well as expensive utensils buried with a body. Such finds undoubtedly indicate that a grave belongs to a once rich person. Some of the deceased, probably for the purpose of preparing them for the afterlife, were buried in chariots and wagons in a pose that has seemingly resembled a journey to the next world.

Among the artifacts were two and four wheeled vehicles made of local oak and elm with carving. They are among the best in the world of this kind of carts. Burial of horses along with the deceased is also an evidence of the development of horse breeding and cultivation in Armenia. In addition to two and four wheeled wagons, other valuable objects were found in the graves of Lchashen – bronze statuettes of oxen, a frog cast from gold, and 25 other gold items made in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, probably from gold mined at Zod (SE Gegharkunik marz).

Another valuable find is a colorful ceramic ware with dotted and ornamented patterns, which were later replaced with shiny black pottery. Wooden items (spoons, ladles, glasses, buckets, tables) are also of great interest to researchers in terms of studying the life of that period. Finally, it is impossible not to mention the cuneiform writing of Urartian king Argishti I, in which he mentions the capture of the city of Ishtikuni. Some researchers believe that Lchashen and Ishtikuni are the same settlements.

We know that the dragon stones probably are not later than the end of the MBA II (defined here as 1800 BC - 1600 BC), since a dragon stone has been found reused on a burial in Lchashen dated to the 1800 BC - 1500 BC (Khanzadyan 2005).💀

Urartu

The written language that the Urartu kingdom's political elite used is retroactively referred to as Urartian, which is attested in numerous cuneiform inscriptions throughout Armenia and Eastern Turkey. It is unknown what language was spoken by the peoples of Urartu at the time of the existence of the Kingdom of Van, but there is evidence of linguistic contact between the proto-Armenian language and the Urartian language at an early date (sometime between the 3rd – 2nd millennium BC), occurring prior to the formation of the kingdom.

The Urartian language is an ergative-agglutinative language, which belongs to neither the Semitic nor the Indo-European language families, but to the Hurro-Urartian language family, which is not known to be related to any other language or language family, despite repeated attempts to find genetic links. Examples of the Urartian language have survived in many inscriptions, written in the Assyrian cuneiform script, found throughout the area of the Kingdom of Urartu. Although, the bulk of the cuneiform inscriptions within Urartu were written in the Urartian language, a minority of them were also written in Akkadian (the official language of Assyria).

The presence of a population who spoke Proto-Armenian in Urartu prior to its demise is subject to speculation, but the existence of Urartian words in the Armenian language and Armenian loanwords into Urartian suggests early contact between the two languages and long periods of bilingualism. The presence of toponyms and tribal names of probable Proto-Armenian etymologies which are attested in records left by Urartian kings, such as Uelikuni, Uduri-Etiuni, and Diasuni, further supports the presence of an Armenian speaking population in at least the Northern regions of Urartu.

It is generally assumed that Proto-Armenian speakers entered Anatolia around 1200 BC, during the Bronze Age Collapse, which was three to four centuries before the emergence of the Kingdom of Van. However, recent genetic research suggests that the Armenian ethnogenesis was completed by 1200 BC, making the arrival of an Armenian-speaking population as late as the Bronze Age Collapse unlikely. Regardless, the Urartian confederation united the disparate peoples of the highlands, which began a process of intermingling of the peoples and cultures (probably including Armenian tribes) and languages (probably including Proto-Armenian) within the highlands. This intermixing would ultimately culminate in the emergence of the Armenian language as the dominant language within the region.

Urartu had different names throughout history:

Van: The name Kingdom of Van (Urartian: Biai, Biainili, Վանի թագավորություն) derived from the Urartian toponym Biainili (or Biaineli), which was probably pronounced as Vanele (or Vanili), and called Van (Վան) in Old Armenian, hence the names "Kingdom of Van" or "Vannic Kingdom".

Nairi: Boris Piotrovsky wrote that the Urartians first appear in history in the 13th century BC as a league of tribes or countries which did not yet constitute a unitary state. In the Assyrian annals the term Uruatri (Urartu) as a name for this league was superseded during a considerable period of years by the term "land of Nairi". However, the exact relationship between Urartu and Nairi is unclear. While the early Urartian rulers referred to themselves as the kings of Nairi, some scholars have suggested that Urartu and Nairi were separate polities. The Assyrians seem to have continued to refer to Nairi as a distinct entity for decades after the establishment of Urartu until Nairi was totally absorbed by Assyria and Urartu in the 8th century BCE.

Vocabulary

Armenian in its native tongue is called Hayeren (Haieren). Old Armenian had preserved to some degree the general morphological character of older Indo-European languages based on the inflexion of nouns and verbs.

Armenian language does not have a concept of gender unlike most of the Indo-European languages. In my opinion some numerals in Armenian are of a substrate origin, for example a word for number two երկու (erku) in its origins is more comparable to Kartvelian Svan: ჲერუ (yeru), Neo-Aramaic: ܐܶܬ݂ܶܪ (ʾeṯər), Mandarin Chinese: 二 (èr), Chukchi: ӈирэӄ (ŋireq) or Old Turkic: 𐰚𐰃 (eki). The number three երեքը (ereku) follows a similar pattern with Ainu: レ (re), Chukchi: ӈыроӄ (ŋəroq), Ossetian: ӕртӕ (ærtæ), Basque: hiru, iru. Those words might be of Eastern Hunter-Gatherer origin.

Below is a list of Indo-European cognates in Armenian language:

dog: շուն (šun)

dog: շուն (šun)- Shina: śun

- Sanskrit: शुनि (šuni)

- Latvian: suns

- Old Prussian: sunnis

- Lithuanian: šuõ (genitive: šuñs)

- Sanskrit: शुनः (śunaḥ) (genitive)

- Kashmiri: ہوٗن (hūn)

Only Baltic and Indo-Aryan branches of Indo-European languages form a strict connection here.

- snake: աւձ (awj, auż, ąż)

- Old Polish: anż, ąż

- blood: արիւն (ariwn, aryun)

The other translation for this word in Armenian is: "kin, kinship, kinsman". According to this etymology "aryan" could literally mean "a blood brother". The other form of this word is: արեան- (arean-).

- great, big: մեծ (mec)

- Persian: مه (meh)

- Ancient Greek: μέγας (mégas)

- Hittite: 𒈨𒂊𒅅𒆠𒅖 (me-e-ek-ki-iš) ("numerous")

- Polish: moc

- Czech: moc

- Sanskrit: महा (mahā́)

- Latin: magnus

- Gothic: 𐌼𐌹𐌺𐌹𐌻𐍃 (mikils)

- English: much

- Tocharian B: māka

- bone: ոսկր (oskr)

- Greek: οστό (ostó)

- Slavic Macedonian: коска (koska)

- Belarusian: костка (kostka)

- Polish: ość (fishbone)

- Latvian: asaka (fishbone)

- Lithuanian: ašaka (fishbone)

Sanskrit अस्थि (ásthi) and Hittite ḫa-aš-ta-a-i do not form a connection here.

- heart: սիրտ (sirt)

- Old East Slavic: сьрдьце (sĭrdĭce)

- Latgalian: sirds

- Latvian: sirds

- Lithuanian: širdis

- Punjabi: ਹਿਰਦਾ (hirdā)

- to die: մեռանիմ (meṙanim)

- Old East Slavic: мерети (mereti)

- Belarusian: ме́рці (mjérci)

- Hittite: me-er-zi (merzi)

- Old Church Slavonic: мрѣти (mrěti)

- Polish: mierzić (to disgust)

- Polish: marnieć

- Sanskrit: मरति (márati), म्रियते (mriyate)

- Latin: morior

- aurochs: տուր (tur)

- Polish: tur

- Russian: тур (tur)

- Lower Sorbian: tur

- Swedish: tjur

- Latvian: taurs

- Lithuanian: tauras

- Greek: ταύρος (tauros)

- Estonian: tarvas

- Gaulish: taruos

- Welsh: tarw

- Old Irish: tarb

- Latin: ūrus (of Celtic origin according to Julius Caesar)

- Old English: ūr

- Romanian: bour

- goat: քոշ (kʿoš)

- Czech: kozel

- Polish: koziol, koza

- hedgehog: ոզնի (ozni)

- Old East Slavic: ожь (ožĭ)

- Russian: ёж (jož), ёжик (jóžik)

- Belarusian: во́жык (vóžyk)

- Phrygian: ἔζις (ézis)

- Latvian: ezis

- Lithuanian: ežys

- old: հին (hin)

- Younger Avestan: hana

- Breton: hen

- Cornish: hen

- Welsh: hen

- Ancient Greek: ἕνος (hénos)

- Old Irish: sen

- Ket: синьсь (sīn) (Siberian shamans)

This word is most probably of Eastern Hunter-Gatherer origin.

- tongue: լեզու (lezu)

- Lithuanian: liežùvis

- to lick: լիզեմ (lizem)

- Polish: lizać, liżę, lizem (to lick, I lick)

- Lithuanian: liežti (to lick)

- eye: աչք (ačʿka)

- Polish: oczko (small eye)

- cauldron: կաթսա (katʿsa)

- Latvian: katls

- Sanskrit: कटोर (katora)

- Finnish: kattila

- Estonian: katel

- Gothic: 𐌺𐌰𐍄𐌹𐌻𐍃 (katils)

- Latin: catīllus

- ember (glowing coal or wood): պող (poł)

- Central Kurdish: پۆل (pol)

- Kermanic: polozm

- Armenian: պող (poł) ("fire")

- Polish: palić ("to burn")

- Polish: popiół ("ash" - that what is after "po" + fire "piol")

- Polabian Drevani: pipel

- Upper Sorbian: popjeł

- Bulgarian: пе́пел (pépel)

- Lithuanian: pelenai ("ashes")

- Old Prussian: pelanne ("ashes")

- head: գլուխ (glux, geluh)

- Old Prussian: gallū, galwo

- Latvian: galva

- Lithuanian: galva

- Hittite: h̬alaaš

- Old Church Slavonic: глава ⰳⰾⰰⰲⰰ (glava)

- Serbo-Croatian: гла́ва, gláva

- Latgalian: golva

- Kashubian: gôłwa

- Russian: голова́ (golová)

Only Baltic and Slavic branches of Indo-European languages form a strict connection here.

- bear: արջ (ars)

- Breton: arzh

- Avestan: arṣ̌a

- Ossetian: арс (ars)

- Mazanderani: ارش (arš)

- Albanian: ari

- Occitan: ors

- ant: մրջյուն (mrjyun)

- Southern Kurdish: مرۊژ (mrüj)

- Albanian: morr

- Polish: mrówka

- Ancient Greek: μύρμηξ (múrmēx)

- water: ջուր (ǰur)

- Lithuanian: jūra (sea)

- Sami: jaura (lake)

- Livonian: jõra (lake)

- Finnish: järvi (lake)

- Estonian: järv (lake)

- Latin: ūrīnō (to dive, to plunge into water)

- cow: կով (kov)

- Latvian: govs

- Tocharian A: ko

- Tocharian B: keu

- Old Church Slavonic: говѧдо ⰳⱁⰲⱔⰴⱁ (govędo)

- door: դուռ (duṙ), դուռն (duṙn)

- Younger Avestan: duuarəm, duuarə

- Old Dutch: duri

- Gutnish: dur, duri

- Old High German: turi

- Upper Sorbian: durje

- Lithuanian: durys

- Old English: duru

- Old Saxon: duru

- Ossetian: дуар (duar)

- Assamese: দুৱাৰ (duar)

- Old Norse: dyrr

- Ancient Greek: θῠ́ρᾱ (thúrā)

- daughter: դուստր (dustr)

- Old Church Slavonic: дъщи ⰴⱏⱋⰻ (dŭšti)

- Sanskrit: दुहितृ (dúhitṛ)

- Hindi: दुहितृ (duhitŕ)

This could come from a Mitanni influence or it is a common Sintashta source.

- skin: կաշի (kaši)

- Russian: кожа (koža)

- white: սպիտակ (spitak)

- # Old Georgian: სპეტაკი (sṗeṭaḳi)

- Avestan: spaēta

- Latvian: spīdēt (to shine)

- hoarfrost: սառն (saṙn)

- Latvian: sarma

- Lithuanian: šarma

- Persian: سرما (sarmā)

- Old Norse: hjarn

- Finnish: härmä, härm

- Ukrainian: сере́н (serén)

- Old Polish: śron

- Church Slavonic: срѣнъ (srěnŭ)

- nerve, vein, sinew: ջիլ (ǰil, dżil, żil)

- Old Church Slavonic: жила ⰶⰹⰾⰰ (žila)

- Old Czech: žíla

- Polish: żyła

- Lower Sorbian: žyła

- Upper Sorbian: žiła

- Russian: жи́ла (žíla)

- Latvian: dzīsla ("vein")

- Lithuanian: gysla ("vein")

- Old Prussian: gislo ("vein")

- lynx: լուսան (lusan)

- Middle Low German: lūs, los

- Luxembourgish: Luuss

- Middle English: lusk

- Latvian: lūsis

- Lithuanian: lūšis

- Old Prussian: luysis

- Lower Sorbian: lys

- Upper Sorbian: lys

- Ancient Greek: λύγξ (lúnx)

A strong Corded Ware Culture connection

- fish: ձուկն (jukn, dsukn), ձուկ (juk, dsuk)

- Old Prussian: suckis (sukkis, zukkis)

- Ancient Greek: ἰχθῡ́ς (ikhthū́s) (probably from *sikhtus)

- Lithuanian: žuvis

- Latgalian: zivs

- Latvian: zivs

- meat: միս (mis)

- Albanian: mish

- Tocharian B: misa

- I am: ես եմ (yes yem)

- Lativan: Es esmu

- Polish: Ja jestem

- you are: դու ես (du yes)

- Polish: ty jesteś

- Lithuanian: tu esi

- Ukrainian: ти є (ty ye)

- I will give: Ես կտամ (yes ktam)

- Polish: Ja dam

- Albanian: me dhanë (to give)

- ten: տասը (tasy)

- Old Avestan: dasā

- Sanskrit: दश (dáśa)

- Ossetian: дӕс (dæs)

- Indus Kohistani: däš

- Shumashti: däs

Another Mitanni connection

- four: չորս (čors)

- Parachi: čōr

- Tajik: чор (čor)

- Bengali: চার (car)

- Gujarati: ચાર (cār)

- Tajik: чаҳор (čahor)

Lithuanian: keturi or Old Church Slavonic četyre indicate a later innovation in those branches. Indo-Aryan languages preserve the Sintashta related Armenian čor. Parachi language shown above is spoken around Kabul in Afghanistan.

- Change of P to H:

- fire: hur

- Greek: πῦρ (pûr), πυρά (purá)

- Hittite: pahhur

- father: հայր (hayr)

- Latin: pater

- Ancient Greek: πατήρ (patēr)

- Sanskrit: पितृ (pitṛ)

The compound -yr in hayr comes from an earlier -tr and h- in Armenian comes from ph-, so the original form for father was *phatr. Same goes for մայր (mayr) ("mother") from *matr and բայր (bayr) ("brother") from *batr.

- five: հինգ (hing) (*ping, *pink)

- Phrygian: πινκε (pinke)

- Shughni: пӣнӡ (pīnʒ)

- Pashto: پنځه (pinźë́)

- Tocharian B: piś

- Old Welsh: pimp

- Messapic: penka-

- Lithuanian: penki

- Old Prussian: pēnkjāi

- Latvian: pieci

- Upper Sorbian: pjeć

- Old Occitan: cinc

This one could even be a proto form of initial H that later on changed to usual K or unusual P.

- Phrygian-Greek-Armenian as a Balkanic branch:

- man: այր (ayr) -> առն (aṙn) (genitive sg.)

- Phrygian: αναρ (anar)

- Greek: ἀνήρ (anḗr) -> ἀνδρός (andros)

- name: անուն (anun)

- Gaulish: anuana

- Old Welsh: anu

- Primitive Irish: ᚐᚅᚋ (anm)

- Ancient Greek: ὄνομα (ónoma), ὄνῠμᾰ (ónuma)

- Phrygian: ονομαν (onoman)

- Hittite: 𒆷𒀀𒈠𒀭 (lāman)

- Albanian: êmën

- warm: ջերմ (ǰerm)

- Phrygian: Γέρμη (Gérmē)

- Ancient Greek θερμός (thermós)

- Albanian zjarr

- Polish: żar

- Old Prussian: gorme

- Sanskrit: घर्म (gharmá)

- regret, remorse, grief: զղջալ (złǰal), զեղջ (zełǰ)

- Polish: żal

- Bulgarian: жаля́ (žaljá)

- Croatian: žȁliti

- Belarusian: жаль (žal')

- Ukrainian: жаль (žalʹ)

- tooth: ատամն (atamn)

- Ancient Greek: ὀδούς (odoús)

- Ionic Greek: ὀδών (odṓn)

- nine: ինը (inu), ինն (inn)

- Greek: εννέα (ennéa)

- Tocharian A: ñu

- Icelandic: níu

- Gothic: 𐌽𐌹𐌿𐌽 (niun)

- one: մի (mi)

- Ancient Greek μία (mía)

DNA

The Indo-European speaking Catacomb Culture (2800 BC - 1700 BC) is sometimes considered ancestral to Mycenaean Greeks, Phrygians and Thracians. More recently, scholars have suggested that this culture also provided a common background for Armenian. In a February 2019 study published in Nature Communications the remains of five individuals ascribed to the Catacomb Culture were analyzed. Three males were found to be carrying the R1b1a2 (R1b-M269) Y-DNA haplogroup, just like males in the later Bell Beaker Culture. One Armenian Kura-Araxes sample carried the Y-DNA haplogroup R1b1-M415 (from R1b-M269; also called R1b1a1b-CTS3187).

For all four Armenian populations analyzed in a 2011 study, the most prevalent major haplogroups were pure R-M207 without deeper R1b or R1a clades (38% in Ararat Valley, 36% in Gardman, 33% in Lake Van and Sasun) and J-M304 (38%, 36%, 43% and 27%, respectively). R1a among Armenians varies only between 4% and 6% of the whole modern population, while the R1b haplogroup varies between 19% and 37% (in Ararat valley).

Of the lineages within haplogroup R, the R1b1b1 (R1b-L23) predominates in Ararat Valley (33%), Gardman (31%) and Lake Van (32%). Furthermore in Ararat Valley there are individuals belonging to the paraphyletic haplogroup R1b1b (R1b-M269). The Sasun collection, meanwhile, contains comparable distributions of haplogroups R1b1b1 (R1b-L23) at around 15% and R2-M124 at around 17% (common in India). It should be noted that only low frequencies of haplogroup R1a1 (R1a-M198), which has been associated with the Indo-Aryan expansions were observed in Ararat Valley (0.9%), Gardman (5.2%) and Sasun (0.9%).

Large proportion of individuals in Armenia and Northwest Iran belonged to the R1b-Z2103 → R1b-M12149 Y-DNA haplogroup during the 2nd and early 1st millennium BC, providing a genetic link with the Yamna Culture. Two Bronze-to-Iron Age sites with substantial sample sizes (7x Bagheri Tchala and 12x Noratus) have contrasting haplogroup distributions dominated by R1b-M12149 (from R1b-Z2103) and I2a-Y16419 (from Balkans) respectively, suggesting founder events, high genetic drift, or a patrilocal mating system around 1000 BC in Armenia[6].

Three samples from Karashamb LBA Cemetery around 1420 BC - 1250 BC carried the descendant haplogroups of R1b-Z2103: I19344 Y-DNA R1b-FGC48354 (from R1b-Y18961 from R1b-Z2106 from R1b-M12149) mtDNA T1a (local, also common in Romania), I19336 Y-DNA R1b-Y13369 (from R1b-M12149) mtDNA K1a12a, I19335 Y-DNA R1b-Y13369 (R1b1a1b1b) mtDNA K1a23[6].

During the same period at Hasanlu in Northwest Iran, many individuals have no trace of Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer ancestry at all despite the presence of R1b-M12149 there, suggesting that the initial association of this lineage with Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer ancestry on the Steppe had vanished as R1b-M12149 bearers reproduced with Southern Arc individuals without EHG ancestry[6].

One man from the times of Kura-Araxes Culture (after 3000 BC) from Berkaber, Armenia already carried the R1b-V1636 Y-DNA haplogroup[7]. R1b-V1636 (Khvalynsk II related) also appears around 2900 BC - 2800 BC (wrong 3105 BC radiocarbon date) in a man (ART038) from a so called Royal Tomb in Arslantepe, Turkey.

R1a among Armenians appears as: R1a1a (R1a-M198), R1a1a1h (R1a-Z93), R1a1a1h1 (R1a-L342.2, from R1a-Z93; surely Mitanni in origin), R1a1a1i (R1a-Z280), which corresponds to Indo-Iranian, Pomeranian (Northern Poland), Baltic and Eastern European background.

There is a prevalence of Neolithic paternal chromosomes that are associated with the Agricultural Revolution, namely E1b1b1c-M123, G-M201, J1-M267, J2a-M410 and R1b1b1 (R1b-L23), which collectively comprise 77% (58% in Sasun and an average of 84% in Ararat Valley, Gardman and Lake Van) of the observed paternal lineages in the Armenian Plateau. Furthermore, Y-STR variance and haplotype distributions suggest that these lineages were likely introduced into Armenia from the Levant. However, later migrations, such as from Armenia to Europe, do not appear to have been associated with any paternal gene flow.

Religion

Vahagn

Vahagn Vishapakagh (Vahagn the Dragon Reaper) or Vahakn (Armenian: Վահագն) was a god of fire, thunder, and war worshipped in ancient Armenia. Vahagn was identified with the Greek deity Heracles. The priests of Vahévahian temple, who claimed Vahagn as their own ancestor, placed a statue of the Greek hero in their sanctuary.

Fiery hair had he, a flaming beard and his eyes they were as suns!

Vahagn fought and conquered dragons, hence his title Vishabakagh (Dragon Reaper), where dragons in Armenian lore are identified as Vishaps. He was invoked as a god of courage.

On the right is an artwork showing Vahagn (created by Gegart, on CC 3.0)

Astghik

Astłik (Armenian: Աստղիկ) had been worshipped as the Armenian deity of fertility and love, later the skylight had been considered her personification, and she had been the consort of Vahagn. In the later heathen period she became the goddess of love, maidenly beauty, water sources and springs. The Vardavar festival devoted to Astłik that had once been celebrated in mid July was transformed into the Christian holiday of the Transfiguration of Jesus and is still celebrated by the Armenians. As in pre-Christian times, on the day of this fest the people release doves and sprinkle water on each other with wishes of health and good luck.

Her name is the diminutive of Armenian word աստղ (astł) meaning "star". All star goddesses were originally called Night goddesses including the morning and the evening star (Venus) which from Proto-Indo-European *h₂stḗr is cognate to Sanskrit: stṛ́, Avestan: star, Pahlavi: star, Persian: setār, Ancient Greek: astḗr etc.

Her principal seat was in Ashtishat (Taron), located to the North from Muş, where her chamber was dedicated to the name of Vahagn, the personification of a sun-god, her lover or husband according to popular tales, and had been named "Vahagn's bedroom". Other temples and places of worship of Astłik had been located in various towns and villages, such as the mountain of Palaty (to the South-West from Lake Van), in Artamet (12 km from Van). The unique monuments of prehistoric Armenia, vishap "dragon stones" (Arm. višap 'serpent, dragon', derived from Persian), spread in many provinces of historical Armenia – Gegharkunik, Aragatsotn, Javakhk, Tayk and are additional manifestations of her worship.

Vardavar

It is a festival that takes place in July and it is dedicated to Astghik. During Vardavar Armenians pour water over each other. It is a very similar practice to West Slavic "Śmigus-dyngus", "oblévacka" and "Šmigrust".

Aralez, Qursha, Simargl and Senmurv

Armenian Արալեզ are dog-like creatures or spirits, who live in the sky or on mount Massis (Mount Ararat). They were praised with Ara the Beautiful and Shamiram (Semiramis) in Old Armenia. Armenians believed that aralezes descended from the sky to lick the wounds of dead heroes so they could relive or resurrect.

Qursha (Georgian: ყურშა) is a legendary dog from Georgian mythology. He is best known as the loyal companion of the culture hero Amirani. His name means "black-ear", a common Georgian name for dogs. He was said to be born of either a raven or an eagle, and is sometimes depicted as having eagle's wings as a result.

Amirani as the son of the mountain goddess Dali and a mortal hunter was a demigod of enormous strength. He traveled the earth challenging "demons and dragons alike," until he decided that there are no worthy opponents left for him and issues a challenge to God himself. God chains him to a pole inside a mountain for his defiance and his faithful hound Qursha is trapped along with him. Qursha licks Amirani's chains constantly, weakening them more and more until Amirani is almost able to escape. However, every year they would be renewed just before Q'ursha could free Amirani.

Simargl or Semargl is a deity or mythical creature in East Slavic mythology, depicted as a winged lion or dog. His wife is Kupalnitsa, goddess of night. He is also a father of Kupalo and Kostroma. Simargl is also the father of Skif and the founder of Cythia. An idol of Semargl was present in the pantheon of Great Prince Vladimir I of Kiev. It may be the equivalent of Simurgh (Senmurv, Sēnmurw) in Persian mythology, which is also represented as a griffin with a dog body.

Hetanism

Hetanism is a growing ethnic religious movement in Armenia. One survey suggest that indigenous Armenian religion is widespread and accepted by the population to the same degree as Christianity is. This may be due to the fact that there is no conflict between the Arordineri Ukht (the major Hetan organization) and the Armenian Apostolic Church. They coordinate their efforts in preserving Armenian cultural identity and in fighting foreign forces. The Arordineri Ukht is even supported by the ruling Republican Party of Armenia, which in turn bases its ideology on tseghakron (native religion) and on the Hetan sacred book Ukhtagirk. "Fire and sword" rituals of the Hetan tradition are often organized on the site of Apostolic churches and patronized by Apostolic priests.

Armenian Neopagans worship the gods of a reconstructed Armenian pantheon: Haik, Aray, Barsamin, Aralez, Anahit, Mihr, Astghik, Nuneh, Tir, Tsovinar, Amanor, Spandaramet, Gissaneh, with a particular emphasis on the cult of the solar god Vahagn. They have re-consecrated the Temple of Garni (a Hellenistic-style temple rebuilt in 1975), originally a temple to Mihr, to Vahagn, and they use it for regular worship and as a center of activity.

Conclusion

The source of modern Indo-European Armenian language most probably lies in the Catacomb Culture or Sintashta Culture from Eastern Europe, which spoke a language most similar to Balto-Slavic, Indo-Iranic and Graeco-Phrygian branches of the Indo-European languages. Before the year 2000 BC or 2400 BC people in Armenia most probably spoke a language similar to this of Colchis and Iberia or a Hurrian language.

Proto-Armenians invading those lands are historically comparable to Turks invading Anatolia or Hungarians invading the lands next to Slovakia and Czechia. The invading minority imposed their language on a majority that spoke a different substrate language, creating a completely new mixed language. That is why some of those Georgian and Armenian "borrowed" words do not have to be borrowed at all and they could be cognates that originated in the same ancestor language.

In Armenian language there are certainly words dating back to Akkadian times: կնիք (knikʿ) meaning "stamp" or "signet", ուրագ (urak) meaning "adze". There are also Hurrian words such as: անագ (anag) meaning "tin" or a word for a famous Armenian pomegranate: նուռն (nurn).

A word of Kartvelian origin is for example: ծանր (canr) meaning "weight" or ծեփ (cepʿ) meaning "plaster".

The Y-DNA R1a haplogroup has been found in 5% of Armenians and at higher concentrations in the following Northern Caucasian groups (to the North of Georgia): 27.5% of Karachays & Balkars (Scythian R1a-Z2123 from R1a-Z93[7][8]), 12.5% of Kumyks, Kabardians & Cherkessians, 10% of Adyghes, Nogays, Karanogays & Abkhazes. Neither the Armenians nor the Caucasian groups seem to be of Slavic origin as evidenced by a map of subclade R1a1a7 (R1a-M458+), meaning the lands around Poland and Belarus were not the source of this haplogroup in Armenia. We have to look to the East (Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India) or to the North (Russian plains) for an explanation of the presence of R1a in Armenia.

In a 2003 study, Nasidze and others examined mitochondrial and Y-DNA haplogroup variation in the Caucasus in an attempt to determine if the genetic evidence would support language shift from Caucasian to Indo-European in Armenia, and Caucasian to Turkic in Azerbaijan. The study found that the Armenians and Azerbaijani are genetically closer to their Caucasian-speaking neighbours than to Indo-European speaking or Turkic speaking people outside the region. Based on the genetic data Nasidze and others proposed that language shift occurred in Armenia and Azerbaijan without a large influx of people from outside the region (2003: 259-260).

Marc Haber et al. paper shows that Armenian cluster started to form aproximatively around 2500 BC (between 3000 and 2000 BC) and there is no new admixture after 1200 BC. Armenian language appearing in this region after 1200 BC is impossible. Haak et al. study shows that R1b-Z2103 was already present in Yamna Culture and there is a short route around the Black Sea to Armenia from this region. Nowadays 30% of Armenian Y-DNA belongs to haplogroup R1b and the vast majority to the R1b-L584 subclade of R1b-Z2103 (from R1b-L23).

After 2000 BC there is a new wave of archaeological influx in Armenia. The newcomers founded the Trialeti-Vanadzor Culture (2400 BC - 1700 BC) that has strong Indo-European traits like big burial mounds (kurgans) and cremation burials. This culture can be associated with Proto-Armenians. The Trialeti Culture then reaches its peak around 1700 BC (at this period the Armenian language is on the same stage of development as the Mycenean Greek in Greece) and later evolves to more homogenous Metsamor-Lchashen Culture all over the Armenian Highlands. This process of homogenization ends around 1300 BC in accordance with Marc Haber genetic admixture data.

Article first published on the 16th of July 2020. Article updated on the 8th of November 2021 with new genetic data on the Lchashen-Metsamor and Trialeti cultures. 7th of September 2022 update with R1b-Z2103 in Hasanlu and Bronze Age Armenia.